Meta’s €1.2 Billion GDPR Fine: Why It Still Matters in 2025

If you search Google for all the GDPR fines Meta has received over the years, the list of articles can be quite confusing.

Google’s AI overview can provide a clear distinction (a topic for another article, for sure) of the types of fines, ranging from penalties for inadequate data protection measures to illegal bases for processing user data for personal advertising on Facebook and Instagram, as well as scraping issues, among others.

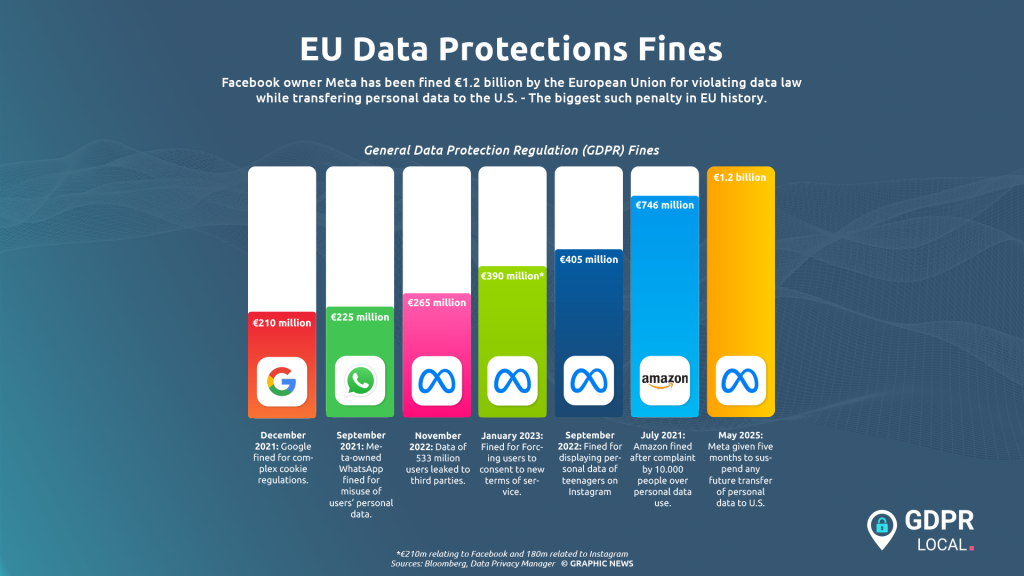

The largest fine, a record-breaking €1.2 billion, was imposed back in May 2023.

That penalty was for one specific reason: unlawfully transferring the personal data of European Facebook users to the United States.

Even now, this 2023 ruling remains a critical issue for any business that moves data between the EU and the US.

The decision exposed a fundamental, and still unresolved, conflict between EU privacy rights and U.S. surveillance laws.

With this article, we will delve into each detail, examining the regulations and the reasoning behind the penalty.

More importantly, we will break down the implications for your business and guide you on how to manage data privacy effectively today.

Why Meta Was Fined €1.2 Billion Under GDPR

Regulators fined Meta for one core violation: illegally transferring the personal data of European users to the United States. This action directly breached the international transfer rules outlined in Chapter V of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The fundamental problem is a conflict between U.S. surveillance laws and the privacy rights guaranteed in the EU. A landmark court ruling, known as Schrems II, found that U.S. law does not adequately protect EU data from access by American intelligence agencies.

The €1.2 billion penalty specifically covers Meta’s illegal data transfers that continued after the Schrems II decision was made on July 16, 2020.

The case stems from a complaint filed by privacy activist Max Schrems nearly a decade earlier.

What This Historic GDPR Fine Means for Big Tech and Data Privacy

Meta’s €1.2 billion penalty was a clear warning to every company moving data between the EU and the US. It signalled a new era of regulatory risk, transforming abstract legal debates into concrete business threats.

Regulators didn’t only issue a fine; they also ordered Meta to take two critical actions:

• Suspend future transfers: Stop all transfers of European user data to the U.S. within five months.

• Bring processing into compliance: Stop all unlawful processing and storage of data that has already been transferred to the U.S. within six months.

The second order requires Meta to either delete historical EU user data from its U.S. servers or move it back to the EU.

For businesses, these operational orders are a far greater threat than the fine itself. They prove that regulators are prepared to halt core business functions, not just issue financial penalties. The ruling also intensified pressure on policymakers to create a stable legal framework for transatlantic data flows.

While a new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework is now in place, privacy advocates are already challenging it.

“If you are unsure of your current practices, we at GDPRLocal can help.”

Infographic: Timeline of the decision

A Landmark Case in Data Protection: The Meta EU Fine Explained

The path to the €1.2 billion fine was not straightforward and highlights a critical power dynamic in GDPR enforcement.

Initially, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission (DPC), Meta’s lead regulator in the EU, decided not to fine the company for the illegal data transfers.

However, several other data protection authorities across Europe objected to this lenient approach, escalating the case.

The dispute was sent to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), the body responsible for ensuring GDPR is applied consistently across the EU. The EDPB overruled the Irish DPC and issued a binding decision, forcing the Irish regulator to take significantly stronger action.

The EDPB’s final orders were clear:

• Impose a fine: The EDPB mandated a financial penalty for the infringement.

• Stop future transfers: Meta was ordered to suspend all future transfers of EU user data to the U.S. within five months.

• Address past transfers: Meta was also ordered to stop all unlawful processing, including the storage, of EU data that had already been illegally transferred to the U.S. within six months.

The EDPB justified the record-breaking fine by pointing to several “aggravating factors.” It found Meta’s violation to be “very serious,” noting the transfers were “systematic, repetitive and continuous” and involved the data of millions of Europeans.

Most importantly, the EDPB concluded that Meta had acted with “at least the highest degree of negligence.”

Due to this severity, the EDPB instructed that fines should begin at 20% and can increase up to the full amount allowed under the GDPR.

GDPR Background

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a landmark privacy law of the European Union. It governs how organisations handle the personal data of anyone residing in the EU. Effective as of May 25, 2018, its rules are designed to give individuals control over their data.

The law defines “personal data” broadly as any information that can be used to identify a person, from a name or email address to an IP address or location data.

Under GDPR, individuals have enforceable rights, including:

• The right to access their data.

• The right to correct inaccurate information.

• The right to have their data deleted.

For businesses, GDPR establishes clear obligations.

You must have a valid legal basis, like explicit consent, to collect and process personal data.

You are also required to implement strong security measures to protect that data and to report breaches to authorities, often within 72 hours.

Most importantly, the GDPR has a global reach. It applies to any company, anywhere worldwide, that supplies products or services to individuals in the EU or monitors their behaviour.

This is why a U.S. company like Meta is subject to these rules and the authority of EU regulators.

How the GDPR Regulates International Data Transfers

The GDPR’s core principle for international transfers is simple: your data’s protection must travel with it.

When you send personal data outside the European Economic Area (EEA), the level of protection it receives cannot be weakened. These rules apply whether you are sharing data with a partner, a supplier, or using a cloud service provider based in another country.

When does a transfer of personal data outside the EEA occur?

A “transfer” happens when three conditions are met:

1. A company (acting as a controller or processor) is subject to the GDPR.

2. That company sends or makes personal data available to another company.

3. The receiving company is located in a country outside the EEA.

Even giving a U.S.-based parent company remote access to the HR records of an EU subsidiary is considered a transfer.

How to transfer personal data outside the EEA?

You cannot simply send data to any country. GDPR provides a strict hierarchy of legal mechanisms for transferring data outside the EEA. These transfer rules are an additional requirement. You must still comply with all other GDPR principles, like having a legal basis for processing and practising data minimisation.

There are different compliant ways to transfer data:

1. Data transfers on the basis of an adequacy decision

This is the most straightforward path for international data transfers.

An adequacy decision is a formal “green light” from the European Commission. It means the Commission has officially recognised a specific country as providing data protection that is similar to what the GDPR requires. If a country has an adequacy decision, you can transfer personal data there without needing any extra safeguards for the transfer itself. It becomes comparable to transferring data within the EEA.

The European Commission regularly reviews these decisions to ensure the country’s legal framework continues to provide adequate protection.

2. Data transfers using Appropriate Safeguards

This is the path you must take when sending data to a country that does not have an adequacy decision.

The most common tool here is Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). SCCs are pre-approved legal contracts issued by the European Commission that bind the company receiving the data to GDPR standards. However, the Schrems II court ruling made it clear that simply signing SCCs is no longer enough.

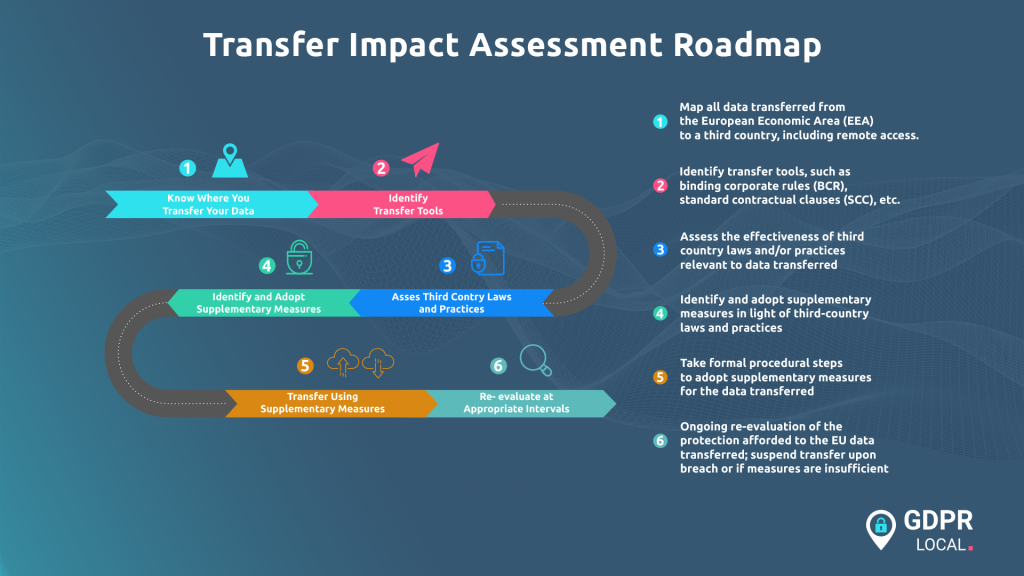

You, the data exporter, are now required by law to conduct a Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA) before the transfer takes place. A TIA is your documented analysis to verify if the laws in the destination country, particularly government surveillance laws, prevent the importer from protecting the data as promised in the SCCs. If your TIA identifies risks, you must implement supplementary measures to ensure the data receives protection “essentially equivalent” to what it has in the EU.

These measures can be:

• Technical: Strong encryption where you control the keys, or pseudonymisation where the data cannot be re-identified.

• Contractual: Clauses that require the importer to challenge government requests or be transparent about them.

• Organisational: Strict internal policies for handling data requests and minimising data transfers.

If you cannot find effective supplementary measures to neutralise the risks, the transfer is illegal and must be stopped.

3. Derogations (for specific, limited situations)

In very specific and occasional situations, you may be able to use a “derogation” under Article 49 of the GDPR.

These are narrow exceptions, not a basis for regular, systematic transfers.

Examples include obtaining an individual’s explicit consent for a specific, one-time transfer or when the transfer is absolutely necessary for a contract with that individual.

The Role of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) in Global Data Flows

Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) are pre-approved, non-negotiable legal contracts issued by the European Commission.

They are the most common tool businesses use to legally transfer personal data from the EEA to a country that does not have an adequacy decision. By signing these clauses, the company receiving the data (the “data importer”) contractually commits to protecting that data in accordance with GDPR standards.

The European Commission adopted a new, modernised set of SCCs on June 4, 2021. These new clauses were designed to address complex, modern data processing chains and the legal requirements established by the Schrems II court ruling.

Flexible Modules for Different Scenarios

The new SCCs are modular, allowing businesses to select the clauses that fit their specific transfer scenario :

• Controller-to-Controller (C2C)

• Controller-to-Processor (C2P)

• Processor-to-Processor (P2P)

• Processor-to-Controller (P2C)

Key Obligations Under the New SCCs

The new SCCs impose several critical obligations on the companies using them :

Enforceable Rights: They ensure that individuals whose data is transferred can enforce their rights directly against both the data exporter and importer.

Mandatory Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA): This is the most significant requirement. Before any transfer, the data exporter must conduct and document a TIA. This assessment verifies if the laws in the destination country, particularly government surveillance laws, would prevent the importer from protecting the data as promised in the SCCs.

Government Access Rules: The SCCs include specific obligations for how the data importer must handle access requests from public authorities. This includes notifying the exporter and challenging unlawful requests whenever possible.

The Legal Basis for Data Transfers Between the EU and the US

The €1.2 billion penalty specifically targets Meta’s use of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) in the period following the Schrems II ruling, which invalidated the Privacy Shield framework.

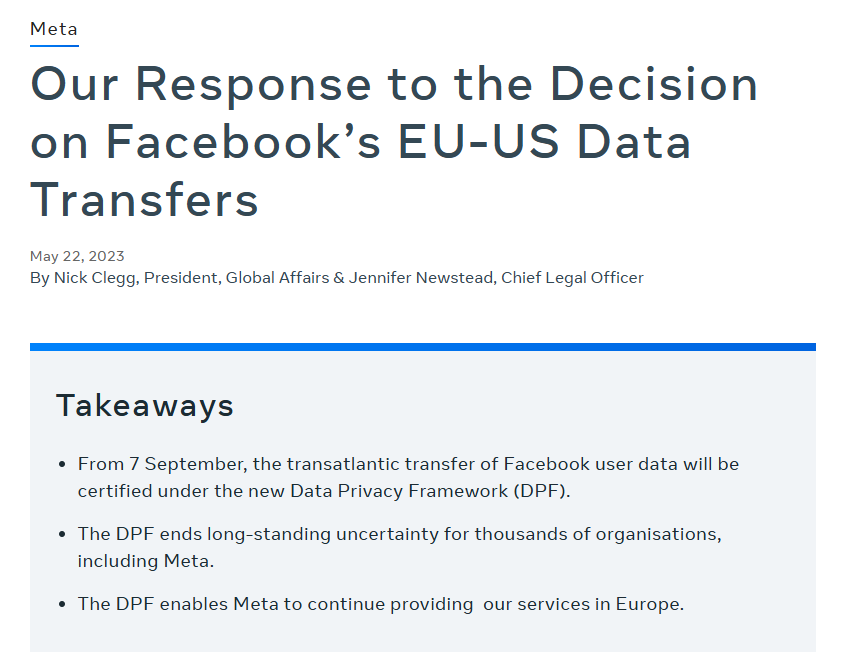

It does not relate to the company’s current reliance on the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF), which was introduced in July 2023.

However, Meta is appealing the fine, and privacy advocates are already challenging the new DPF in court.

This ongoing legal uncertainty is why every organisation must have a well-documented SCC and Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA) process ready as a fallback.

The table below captures the history of EU-US data transfer mechanisms and illustrates why the Meta ruling has implications for every business that moves data across the Atlantic.

| Legal mechanism & GDPR article | Meta’s reliance period | Why Meta used it | What killed/rescued it | Effect on Meta (and everyone else) | Status today |

“Safe Harbour” adequacy decision (Art 45) | 2000 → 6 Oct 2015 | Commission‑approved, no extra paperwork; used by almost every US tech firm | CJEU Schrems I judgment (C‑362/14) struck it down for weak safeguards against US surveillance (Curia) | Forced Meta to scramble for an alternative base within weeks | ❌ Invalid since 2015 |

“Privacy Shield” adequacy decision (Art 45) | 12 Jul 2016 → 16 Jul 2020 | Political replacement for SafeHarbour; Meta recertified each year | CJEU Schrems II (C‑311/18) said Shield still let US authorities snoop, so it too fell (Curia) | Meta (and thousands of firms) pivoted to Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) overnight | ❌ Invalid since 2020 |

Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) (Art 46) | Jul 2020 → May 2023 | Only off‑the‑shelf safeguard left after Schrems II | DPC inquiry found Meta’s SCC package + technical measures insufficient; EDPB ordered a record €1.2 bn fine + transfer ban (Final Decision 12 May 2023) (DAC Beachcroft, EDPB) | Largest GDPR penalty to date; Meta appealed and won a stay, so transfers continued while it looked for a new basis | ⚠️ Still valid, but must be bolstered by a Transfer‑Impact Assessment and “supplementary measures” for most exporters |

EU‑US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) (Art 45) | 7 Sep 2023 → present | Fresh adequacy deal promised “essential equivalence”; Meta switched Facebook transfers on day one | Adequacy decision of 10 Jul 2023; first Commission review (Jan 2024) found it working; NOYB vows new challenge, but no court case yet (European Commission, About Facebook) | Meta’s fine and suspension order are stayed pending appeals (T‑325/23); DPF lets it keep data flowing in the meantime | ✅ Valid but contested, keep SCCs ready as a fallback |

Schrems II: The Court Case That Shaped This Decision

The Meta fine is a direct result of the landmark 2020 court case Schrems II.

It was Austrian privacy advocate Max Schrems who filed the case, as he has long argued that U.S. surveillance laws are fundamentally incompatible with EU privacy rights. His campaign successfully argued that when EU personal data is transferred to the U.S., it can be accessed by American intelligence agencies in a manner that violates the GDPR.

The Schrems II ruling completely changed the rules for transatlantic data transfers, and its impact is felt by thousands of companies today.

The Legal Precedent: From Safe Harbour to Privacy Shield

For years, companies used a framework called “Safe Harbour” to legally transfer data from the EU to the US.

In 2015, following a challenge by Schrems, the EU’s top court invalidated Safe Harbour in a ruling known as Schrems I. The court found the framework did not adequately protect EU data from U.S. government surveillance.

In response, officials created a replacement called the “EU-U.S. Privacy Shield,” which was adopted in 2016. However, this new framework was also challenged, ultimately leading to the pivotal Schrems II decision.

The Schrems II Ruling Explained

On July 16, 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) delivered its Schrems II judgment, which had two monumental consequences:

• It invalidated the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield framework, making it illegal to use for data transfers.

• It established new, much stricter obligations for companies using Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs).

Why the Court Invalidated Privacy Shield

The court’s reasoning was clear and targeted two main issues with U.S. law:

• Disproportionate Surveillance: The CJEU found that U.S. surveillance programs, authorised under laws like Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), allow for bulk access to EU citizens’ data. This access was not limited to what is “strictly necessary and proportionate,” a core requirement of EU law.

• Lack of Legal Redress: The court also ruled that EU citizens had no effective way to challenge this surveillance or seek justice in U.S. courts, violating their fundamental rights.

The New Rules for Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs)

The Schrems II ruling did not ban SCCs, but it fundamentally changed how they must be used.

The court placed a new, heavy responsibility directly on the company sending the data (the “data exporter”). Simply signing SCCs was no longer enough. Businesses are now legally required to perform a case-by-case assessment, known as a Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA), before making a transfer.

This assessment must verify that the laws in the destination country do not prevent the data importer from upholding the protections promised in the SCCs. If the assessment identifies risks (like U.S. surveillance laws), the exporter must implement “supplementary measures” to ensure the data receives protection that is “essentially equivalent” to what it has in the EU.

If effective measures cannot be found, the data transfer is illegal and must be suspended or stopped entirely.

Legal and Regulatory Issues

Why the Use of SCCs Was Not Enough

The core problem for Meta was a direct conflict between private contracts and national law.

However, U.S. surveillance laws, like Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), can legally compel a U.S. company to hand over that data to government agencies.

In any conflict between a private contract and a federal law, the law wins. The Schrems II ruling required Meta to demonstrate that it had “supplementary measures” in place to address this legal gap.

However, both the Irish DPC and the EDPB found that Meta’s measures were insufficient to neutralise the risk.

While Meta used encryption, regulators pointed out that under FISA 702, U.S. authorities could compel the company to provide not only the encrypted data but also the cryptographic keys needed to read it. This rendered the encryption ineffective as a safeguard.

Ultimately, regulators determined that Meta’s SCCs constituted “mere contractual promises” that had no practical effect against the overriding authority of U.S. surveillance law.

Meta’s Defence and Why It Failed

Meta immediately announced it would appeal the decision, calling the fine “flawed, unjustified and unnecessary.”

The company argued that it was being “singled out” for using the same legal mechanism, Standard Contractual Clauses, as thousands of other businesses that transfer data to the U.S.

Its core defence was that the issue is a “fundamental conflict of law” between the U.S. government’s rules on data access and European privacy rights.

Meta maintained that this is a conflict only policymakers can resolve, not individual companies.

Why Regulators Rejected It

Regulators dismissed these arguments, focusing entirely on Meta’s failure to comply with the law as it stood after the 2020 Schrems II ruling.

The Irish DPC and the EDPB found that Meta’s supplementary measures did not adequately protect data from U.S. surveillance laws, such as FISA 702.

While the Irish DPC initially suggested Meta acted in “good faith,” the EDPB overruled this view.

The EDPB concluded that Meta committed the infringement with “at least the highest degree of negligence” by continuing the transfers for years after they were ruled illegal.

Finally, Meta’s hope that a new political deal, the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, would solve the problem was deemed irrelevant.

The new framework could not retroactively excuse years of non-compliance.

The Role of U.S. Surveillance Laws in the Case

The entire case against Meta hinges on a fundamental conflict between EU privacy rights and U.S. national security laws.

The key U.S. law at the centre of this conflict is Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA 702).

FISA 702 permits the U.S. government to conduct targeted surveillance of non-U.S. persons located outside the United States to acquire “foreign intelligence information.” It allows intelligence agencies to compel U.S.-based “electronic communications service providers”, a broad category that includes social media and cloud companies, to turn over user data without a traditional warrant.

This creates a direct clash with the GDPR.

The EU’s top court has repeatedly ruled that this level of access is not limited to what is “strictly necessary and proportionate,” a core requirement of EU law.

The court also found that EU citizens have no effective way to challenge this surveillance or seek legal remedies in U.S. courts.

During the Meta probe, regulators concluded that these laws grant U.S. intelligence agencies “wide discretion,” leaving EU user data exposed.

This is why any unencrypted data arriving on U.S. servers was deemed unprotected, regardless of the contractual promises made in the SCCs.

Why the EU Deemed Meta’s Transfers “Not Essentially Equivalent”

To legally transfer data outside the EU, the GDPR requires that the data receive sprotection that is “essentially equivalent” to the rights it has within the EU.

Regulators decided Meta’s transfers to the U.S. failed to meet this critical standard for three main reasons:

• U.S. law permits disproportionate surveillance. The EU’s top court has repeatedly ruled that U.S. laws like FISA 702 allow government agencies to access EU citizens’ data in ways that are not necessary or proportionate, and without providing the independent oversight or legal remedies guaranteed under EU law.

• Contractual clauses cannot bind a government. While Meta used Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), these are private contracts between companies. They cannot legally prevent U.S. authorities from enforcing national surveillance laws, which means the SCCs alone cannot fix the fundamental legal conflict.

• Meta’s supplementary measures were not enough. Regulators found that Meta’s extra safeguards, including encryption, were insufficient. This is because U.S. law can compel a company to provide not only the encrypted data but also the cryptographic keys needed to make it readable, neutralising the technical protection.

Because these three factors remained unresolved, the EDPB concluded that Meta’s transfers did not guarantee an EU-comparable level of protection and imposed the largest GDPR penalty to date.

Enforcement and Ruling

What the Final Ruling Against Meta Actually Says

The final decision by Ireland’s Data Protection Commission on May 12, 2023, is based on four core findings that explain exactly why Meta’s data transfers were deemed illegal.

• First, regulators confirmed that U.S. law does not offer a level of data protection “essentially equivalent” to the standards guaranteed in the EU.

• Second, the DPC found that neither the old nor the new versions of Standard Contractual Clauses could compensate for this fundamental gap in U.S. legal protections.

• Third, the technical and organisational measures Meta put in place were deemed insufficient to shield EU data from potential access by U.S. intelligence agencies.

• Finally, the ruling confirmed that specific exceptions in the GDPR, known as derogations, cannot be used to legitimise systematic, large-scale data transfers like Meta’s.

Based on these findings, the DPC concluded that Meta had breached the requirements of Article 46(1) of the GDPR.

This led to three major enforcement actions, issued only after the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) overruled the DPC’s initial, more lenient proposal.

The first was a record-breaking €1.2 billion fine.

The second was an order to suspend all future data transfers to the U.S. within five months.

The third was an order to bring all previously transferred data into compliance within six months, which effectively means deleting it or moving it back to the EU.

The EDPB’s Binding Decision Explained

Because several national regulators objected to the DPC’s “no‑fine” draft, the case went to the European Data Protection Board under Article 65.

In Binding Decision 1/2023 (13 April 2023), the EDPB:

• Declared Meta’s infringement “highly serious”.

• Ordered the DPC to impose an administrative fine, setting the starting point between 20 % and 100 % of the legal maximum, and to base the calculation on Meta’s worldwide turnover.

• Required an additional compliance order to stop storing already‑exported EU data in the U.S.

The DPC had no discretion to ignore these directions; under Article 65 (6), it had to “adopt its final decision on the basis of the binding decision.”

Why the DPC Initially Hesitated to Fine Meta

The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC), Meta’s lead EU regulator, initially argued against imposing any financial penalty.

In its draft decision, the DPC stated that a fine would be “disproportionate” and unnecessary.

The regulator reasoned that Meta had acted “in good faith” by using Standard Contractual Clauses, a legal mechanism provided for under the law. The DPC also argued that fining Meta could be viewed as discriminatory, as other tech companies had not faced similar penalties for data transfer violations.

However, several other European data protection authorities strongly objected to this lenient approach.

This dispute triggered the GDPR’s resolution process, which ultimately led to the final decision being escalated to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB).

How the EDPB Overruled Ireland’s Watchdog

The EDPB reviewed each objection, found them “relevant and reasoned,” and overrode the DPC’s position. It instructed Dublin to:

1. Impose a fine calculated per the EDPB’s new five‑step methodology.

2. Order Meta to cease processing, including storage, of EU data already in the U.S.

3. Use Meta Platforms Inc.’s consolidated global turnover in the fine calculation.

Under the GDPR’s consistency mechanism, the DPC was legally bound to implement these measures, which it did on 12 May 2023.

The Technical and Legal Basis for the Record Fine

The legal basis for the fine comes from Article 83(5) of the GDPR, which allows regulators to impose the highest tier of penalties for severe violations.

This tier covers infringements of the core data processing principles, including the rules for international data transfers, and allows for fines of up to 4% of a company’s worldwide yearly income.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) instructed the Irish DPC to impose a fine and determined that the starting point for the calculation should be between 20% and 100% of the legal maximum, given the seriousness of the case.

The EDPB pointed to several “aggravating factors” to justify the historic penalty:

• Duration and Scale: The transfers were “systematic, repetitive and continuous,” involving the personal data of millions of European users over nearly three years.

• Categories of Data: The infringement involved a wide range of personal data, including information that is considered a “special category” under GDPR Article 9.

• High Degree of Negligence: The EDPB found that Meta acted with “at least the highest degree of negligence,” as it was aware that its safeguards were insufficient after the Schrems II ruling, but continued the transfers regardless.

• Economic Benefit: Regulators noted that Meta’s Facebook service was designed in a way that made the unlawful transfers integral to its revenue-generating operations in the EU.

Based on these factors and Meta’s 2022 turnover, the DPC calculated the final penalty of €1.2 billion.

The record fine sends a clear message: paper-based compliance, such as signing SCCs, is meaningless without implementing real-world technical and organisational protections that shield data from foreign surveillance.

Industry Reactions and Responses

How Meta Responded to the €1.2 Billion Fine

Meta immediately announced it would appeal the decision.

In public statements, its executives called the fine “flawed, unjustified and unnecessary.” The company argued that the case highlights a “fundamental conflict of law” between U.S. surveillance rules and EU privacy rights.

Meta maintains that this is a problem for policymakers to solve, not individual companies. Legally, the company announced that it would appeal to the court to pause the deadlines for the fine and the transfer ban. It also filed a case with the EU General Court to annul the EDPB’s binding decision, challenging the regulator’s authority to overrule the Irish DPC.

In parallel, Meta moved to adopt the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF) after it was finalised in July 2023. This new framework provides a legal basis for the company to continue transferring data while its appeals are ongoing.

What Other Tech Giants Are Saying

While other major tech companies have not publicly criticised the ruling against Meta, their actions show they are taking the regulatory risk seriously.

For example, companies like Amazon Web Services quickly self-certified under the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework after its launch, signalling a clear desire for legal certainty in transatlantic data flows.

At the same time, industry groups have lobbied against data localisation rules in Europe. They warn that forcing data to be stored locally would fragment the cloud market and discourage investment, without providing any real privacy benefits.

The risk is not just theoretical; other tech giants are already facing similar scrutiny.

This underscores the reality that the legal principles applied to Meta could impact any major U.S. cloud or tech provider operating in the European Union.

Industry Analysts React to the Record GDPR Fine

Industry analysts framed the decision as a watershed moment, not a one-off penalty for a single tech giant.

Forrester called the fine a “wake-up call” for every business that transfers data from the EU to the U.S.

The ruling proves that European regulators now have the “power and the guts to dismantle a company’s business model, regardless of its size,” to enforce data protection law.

Commentators from the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) noted that the ruling reveals systemic, previously unseen risks, not just dramatic data breaches, that now trigger the largest GDPR sanctions.

Analysts warned that if Meta’s extensive safeguards were deemed insufficient to protect data from U.S. surveillance laws, it is unlikely any other organisation’s current measures would pass the same level of scrutiny.

Statements from Privacy Advocates and Legal Experts

Privacy groups hailed the decision as a long-overdue victory for data protection.

Max Schrems, whose organisation NOYB brought the original complaint, called the outcome a “major blow” to Meta. He predicted the company has “no real chance” of having the decision overturned unless U.S. surveillance laws are reformed.

Regulators echoed the message that the fine was intended as a strong deterrent.

EDPB Chair Andrea Jelinek described Meta’s infringement as “very serious.” She stated that the “unprecedented fine is a strong signal to organisations that serious infringements have far-reaching consequences”.

Legal observers noted that the ruling’s logic could apply to many other companies. The decision’s reasoning could be equally applicable to any internet platform subject to U.S. surveillance laws, such as FISA 702, suggesting broader enforcement to come.

Broader Implications

What This Fine Means for Other U.S. Tech Companies

Analysts view the sanction as a clear warning shot to any U.S. tech company that transfers data from the EU. The ruling’s logic suggests that any internet platform subject to U.S. surveillance laws could be next.

In October 2024, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission fined Microsoft’s LinkedIn €310 million for unlawfully processing user data for targeted advertising. This demonstrates that regulators are actively applying these principles to other major tech firms. In response to the legal uncertainty, many cloud giants, including Amazon Web Services, rushed to self-certify under the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework shortly after its launch.

This was a clear move to find a more stable legal basis and step out of the high-risk spotlight associated with using SCCs and TIAs alone.

Is This the End of Business‑as‑Usual for Global Data Flows?

The Meta decision has accelerated a global trend toward data localisation.

For years, European regulators have questioned routine data transfers to the U.S., citing the same surveillance risks highlighted in the Schrems II case.

National data protection authorities in countries such as France and Germany have advocated for stricter rules, sometimes requiring critical data to be stored on European-owned infrastructure.

In response, major cloud providers are increasingly offering “EU-only” service options, promising to keep European data ring-fenced within the region. This push for “digital sovereignty” is not limited to Europe.

With similar debates happening in other major economies, the era of frictionless, worldwide data routing looks increasingly fragile.

How Companies Should Rethink Their Data Transfer Mechanisms

The Meta ruling makes it clear that a “set it and forget it” approach to international data transfers is no longer a viable strategy.

Moving forward, businesses need a layered defence built on proactive, documented compliance.

• Document every Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA). This is a mandatory, case-by-case analysis is a must conduct before transferring data using SCCs. Your TIA must assess if the laws in the destination country undermine the protections in your contract and document the supplementary measures you implement to close any gaps.

• Encrypt or pseudonymise by default. Regulators now expect technical measures that render intercepted data useless. To be effective against U.S. surveillance laws, encryption keys must be controlled exclusively by the data exporter in the EU, so the U.S. importer cannot be compelled to hand them over.

• Diversify your legal bases. Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) can be an effective tool for transfers within a corporate group. Reserve Article 49 derogations, like explicit consent, only for specific, one-off situations; they are not a solution for regular, systematic data flows.

• Keep an eye on legal changes continuously. Compliance needs regular reassessment. The EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework is under scrutiny, and a court decision may prompt a swift return to the use of Standard Contractual Clauses.

The record Meta fine shows that international transfers are no longer a peripheral compliance task.

They are a strategic, multi-jurisdictional risk that must be integrated into your products, contracts, and technical architecture from day one.

What Companies Can Learn From Meta’s GDPR Fine

Meta’s €1.2 billion penalty shows that standard paperwork cannot outweigh real-world surveillance risks.

Regulators looked past Meta’s contractual assurances and focused on a single question: did U.S. law still allow disproportionate access to EU data?

The answer led to two clear lessons for every business.

First, static compliance policies are a significant liability.

While Meta’s use of SCCs may have been a reasonable approach immediately after the Schrems II ruling, its failure to adapt over the next three years was seen as a critical failure.

Regulators concluded that Meta had ignored a known risk and acted with “at least the highest degree of negligence.”

Second, the volume and duration of non-compliance will dramatically amplify fines.

This indicates that regulators can impose sanctions up to the 4% turnover ceiling for long-running, large-scale violations, even if no data breach has occurred.

The ultimate takeaway is that boards must treat cross-border data transfers as a living risk area, one that requires continuous monitoring of legal and political developments.

The Future of Privacy Shield and Data Privacy Frameworks

When Safe Harbour fell in 2015 and Privacy Shield was invalidated in 2020, transatlantic data flows were thrown into legal chaos.

The European Commission’s third attempt to solve this problem is the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF).

On July 10, 2023, the Commission adopted a formal adequacy decision for the DPF, reaffirming the United States’ “essentially equivalent” status for certified companies.

This new framework was designed to address the specific shortcomings identified in the Schrems II ruling.

It includes new commitments from the U.S. government to limit surveillance and establishes a new redress mechanism for EU citizens.

However, the DPF’s long-term survival is uncertain and depends on two key factors.

The first is the future of U.S. surveillance law, as Congress reauthorised the critical FISA 702 only until April 2026 after heated privacy debates.

The second is the high likelihood of a new legal challenge from privacy advocates.

Max Schrems’ organisation, NOYB, has already signalled it is preparing a “Schrems III” challenge if the new framework proves inadequate.

The Role of the EU‑U.S. Data Privacy Framework

The EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF) is the third attempt by officials to establish a stable legal mechanism for transatlantic data transfers, following the invalidation of the Safe Harbour and Privacy Shield frameworks.

It operates as a voluntary certification program. U.S. companies can self-certify to the U.S. Department of Commerce that they will adhere to a detailed set of privacy principles.

In return, the European Commission treats these certified companies as offering an “adequate” level of data protection.

This adequacy decision enables the flow of personal data from the EU to a DPF-certified company in the U.S. without requiring additional safeguards, such as SCCs.

The European Data Protection Board’s first-year review, conducted in November 2024, deemed the framework “generally effective” but flagged ongoing concerns regarding redress and bulk surveillance.

Industry groups argue the DPF is the only realistic bridge for the massive volume of EU-U.S. trade that relies on data flows, while privacy advocates have signalled their intent to challenge it in court.

How to Audit Your Data Transfer Practices

An effective audit starts by mapping every data flow that leaves the EEA and matching it to a valid legal basis.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) provides a clear roadmap for this process, which is now a mandatory part of compliance.

1. Know your transfers. You must first map all your international data flows. Document what data is being transferred, where it is going, and which vendors or partners are receiving it. This includes remote access from a third country, which also qualifies as a transfer.

2. Identify your transfer tool and assess the risk. For each data flow, identify the legal tool you are relying on, such as the DPF, SCCs, or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs). If you use SCCs or BCRs, you must conduct and document a Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA). This assessment evaluates whether the laws in the destination country, particularly government surveillance powers, undermine the protections in your contract.

3. Implement supplementary measures. If your TIA identifies risks that your legal tool cannot mitigate alone, you are required to implement additional safeguards. Technical measures that render intercepted data useless, like strong encryption with EU-controlled keys, are now the de facto expectation. These can be combined with additional contractual and organisational measures to ensure an “essentially equivalent” level of protection.

4. Document and re-evaluate. You must formally document your reasoning and the measures taken in your TIA, which senior management should sign off on. Finally, compliance is not a one-time task; you must re-evaluate your assessments at appropriate intervals to monitor for any legal or practical changes in the destination country.

The Importance of Transparency and Risk Assessments

Following the Meta fine, regulators expect proactive and transparent disclosure about the risks associated with international data transfers.

This aligns with the core GDPR principles of “lawfulness, fairness, and transparency” and “accountability” found in Article 5.

Your privacy notice, as required by Article 13, must clearly inform individuals about how their data is handled when it is sent abroad.

This includes:

• Explaining the legal tool you rely on, whether it’s the DPF, SCCs, or BCRs, and being transparent about its limitations.

• Describing any supplementary measures you use in plain language, for example, stating that “files are encrypted with keys stored only in the EU”.

• Updating these notices swiftly if a court invalidates a transfer mechanism or a partner’s certification lapses.

This external transparency must be supported by strong internal documentation, specifically your Record of Processing Activities (RoPA) as required under Article 30.

Your RoPA must detail all international transfers, the safeguards in place, and reference your Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs).

Companies that embed TIAs, encryption, and clear board oversight into their operating rhythm will weather the next regulatory storm far better than those that rely on dated paperwork.

Final Thoughts

While the €1.2 billion penalty is eye-catching, the true impact of this case lies in the precedent it sets for future GDPR enforcement.

The ruling validates the EDPB’s power to override a national regulator and impose a fine.

It also proves that regulators will pair financial penalties with corrective actions, such as ordering a company to delete or repatriate unlawfully transferred data.

These elements turn a headline-grabbing figure into a clear roadmap for future enforcement actions.

Why Strong Data Privacy Governance Is Now a Business Imperative

The Meta case has shifted data-transfer risk from a legal compliance issue to a core business and executive-level concern.

Microsoft’s decision to set aside a reserve for a potential GDPR fine indicates that major companies are now factoring this enforcement risk directly into their financial planning. While major U.S. cloud providers rushed to certify under the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, they continue to implement strong supplementary measures.

This acknowledges that strong internal governance must outlast any single political data transfer agreement.

The key takeaway for boards is that this risk is dynamic; surveillance laws, court rulings, and adequacy reviews continually change the compliance landscape.

Evidence is now critical, as regulators will demand to see documented Transfer Impact Assessments and proof of supplementary measures, not just contractual promises.

The EU Sends a Message: Data Privacy Is Non-Negotiable

From the invalidation of Safe Harbour and Privacy Shield to the expected “Schrems III” challenge against the new Data Privacy Framework, the EU has consistently shown it will prioritise fundamental rights over commercial convenience.

The EDPB’s first review of the DPF was generally positive but flagged ongoing concerns about redress and surveillance, thereby maintaining high political pressure.

The EU remains firm in its position: personal data protection is a fundamental right that cannot be compromised for commercial convenience or scale.

Meta’s fine proves that international data flows now live at the intersection of law, technology, and geopolitics.

The companies that will succeed are those that integrate strong privacy governance into their product design and strategic planning from the outset.

Don’t let international data transfers become a risk to your business.

From ad-hoc consultancy to a dedicated Data Protection Officer (DPO), GDPRLocal provides the expertise you need to achieve and maintain compliance.