AI and Intellectual Property: Legal Challenges and Opportunities

Artificial intelligence is transforming the way we create, innovate, and protect intellectual property. As AI systems become increasingly sophisticated at generating content, inventing solutions, and processing vast amounts of data, they’re challenging the fundamental assumptions about creativity, authorship, and ownership that have previously guided intellectual property laws.

For businesses implementing AI tools and AI systems, understanding the intersection of AI and intellectual property has become critical. The legal environment is evolving rapidly, creating both opportunities and risks that require careful evaluation.

Key Takeaways

• Current intellectual property laws generally require human creativity and authorship, rendering AI-generated content ineligible for traditional copyright protection unless it involves significant human involvement.

• The use of copyrighted training data in AI systems raises substantial IP infringement risks, leading to ongoing legal disputes and the need for clearer licensing and regulatory frameworks.

• Patent law presents unique challenges for AI-generated inventions, as most jurisdictions require a natural person to be the inventor, with only limited exceptions, such as South Africa’s controversial DABUS case.

Current State of AI and Intellectual Property Rights

The relationship between AI and intellectual property centres on two fundamental questions: Can AI be protected as intellectual property, and can AI-generated outputs receive IP protection? These questions have sparked intense debate among legal scholars, policymakers, and industry leaders.

Generative AI creates content by recognising patterns in massive datasets containing text, images, audio, and other media. These AI models learn from millions or billions of examples to generate new outputs that can appear remarkably similar to human-created works. This process raises complicated questions about originality, creativity, and the role of human authorship in intellectual property protection.

The current legal framework generally requires human creativity and human authorship for most forms of IP protection. This principle, established long before the advent of artificial intelligence, now faces unprecedented challenges as AI generates increasingly sophisticated content autonomously.

Legal Positions on AI-Generated Content

Major jurisdictions have begun clarifying their positions on AI-generated content and AI-generated works. The United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have all reaffirmed that current intellectual property laws require human involvement for protection. Nevertheless, the specific requirements for human input and the threshold for human creativity remain subjects of ongoing legal development.

Patent offices worldwide are encountering a surge in AI-related applications, from machine learning algorithms to AI inventions in pharmaceuticals and manufacturing. The USPTO reported processing over 60,000 AI-related patent applications in 2023, representing a significant increase from previous years. This growth reflects both the expanding capabilities of AI technology and the business community’s recognition of AI as a valuable IP asset, making it increasingly important to conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) for AI systems.

IP Protection for AI-Generated Content

The question of whether AI-generated outputs can receive copyright protection hinges on the fundamental requirement of human authorship. In most jurisdictions, copyright law explicitly requires a human creator, making AI-generated work ineligible for traditional copyright protection.

The United States has taken an unyielding stance on this issue. The U.S. Copyright Office states that works produced by machines or mere mechanical processes without creative input from a human author cannot be registered. Recent court decisions, including the widely cited Thaler case, have reinforced this position by denying copyright registration for works created entirely by artificial intelligence.

Nevertheless, the distinction between AI-generated content and AI-assisted human creation remains critical. When humans provide substantial creative input, such as selecting prompts, curating outputs, or significantly editing AI-generated material, the resulting work may qualify for copyright protection. The challenge lies in determining the threshold of human creativity required for security.

The United Kingdom presents a unique approach with its provision for computer-generated works. Under UK copyright law, computer-generated works receive protection for 50 years from creation, compared to the life-plus-70-years term for human-authored works. This provision, initially designed for early computer programs, now applies to specific AI-generated outputs where no human author can be identified.

| Jurisdiction | AI-Generated Content Protection | Protection Term | Key Requirements |

| United States | No | N/A | Human authorship required |

| European Union | No | N/A | Human authorship required |

| United Kingdom | Limited (computer-generated works) | 50 years | No identifiable human author |

| South Africa | Yes (limited cases) | Varies | Controversial DABUS decision |

| Japan | No | N/A | Human authorship required |

Patent law presents even greater challenges for AI-generated works. Patent systems worldwide require a natural person to be named as the inventor. The controversial DABUS case, in which an AI system was listed as the inventor, was rejected by central patent offices, including the USPTO and the European Patent Office. Only South Africa granted the patent, creating an international precedent that remains largely isolated.

The practical implications for businesses are significant. Companies using AI tools to create content must carefully document human involvement in the creative process to maintain potential IP rights. This includes keeping records of human input, innovative decisions, and substantial modifications to AI-generated outputs.

Training Data and IP Infringement Risks

One of the most contentious aspects of AI and intellectual property involves the use of copyrighted material to train AI models. Major AI systems are trained on billions of copyrighted images, texts, and other content, often scraped from the internet without explicit permission from rights holders.

Several high-profile lawsuits have emerged targeting this practice. Getty Images filed suit against Stability AI in 2023, alleging that the company used millions of copyrighted images to train its Stable Diffusion model without permission. The lawsuit highlighted how AI systems can reproduce watermarks and stylistic elements from training data, suggesting direct copying of protected works.

The Authors Guild and individual writers have filed similar cases against OpenAI and other companies, claiming that training large language models on copyrighted books constitutes copyright infringement. These cases raise fundamental questions about whether using copyrighted material for AI training falls under fair use or similar exceptions in international copyright law.

The legal environment around training data remains unsettled, with courts applying traditional copyright principles to novel AI technologies. Key factors being considered include:

• The transformative nature of AI training and output generation

• The potential market impact on original creators

• The scale of copying involved in training modern AI models

• The availability of licensing mechanisms for training data

Different jurisdictions are developing varying approaches to text and data mining for AI training. The European Union’s Copyright Directive includes specific exceptions for the use of computational data analysis and scientific research. Nevertheless, these contain opt-out provisions that allow rights holders to prevent their works from being used for AI training.

For businesses implementing AI technologies, these disputes create significant liability concerns. Companies must assess whether their AI tools were trained on potentially infringing datasets and consider the risks of using such systems for commercial purposes. Some organisations are developing policies that require verifying the successful waiting period for proper licensing of training data before deploying AI systems.

The emergence of “clean” training datasets, compiled entirely from public domain or appropriately licensed content, represents one industry response to these concerns. Nevertheless, such datasets are often smaller and may produce less capable AI models, creating a tension between legal compliance and technological performance.

Copyright Challenges in the AI Era

Copyright law faces unprecedented challenges as AI continues to evolve. Traditional copyright frameworks, designed for human creators, struggle to address the unique characteristics of AI-generated outputs and the collaborative nature of human-AI creation.

Originality and Creativity in AI-Generated Content

The originality requirement in copyright law becomes complicated when applied to AI-generated content. Copyright protection typically requires a minimal level of creativity and originality, concepts traditionally associated with human expression. When AI systems generate content based on patterns learned from existing works, determining originality becomes increasingly difficult.

Rights and AI Creations

Moral rights, recognised in many jurisdictions, present additional complications for AI-generated works. These rights, including attribution and integrity, are inherently personal and cannot easily be assigned to non-human entities. This creates gaps in protection when AI systems generate content that might otherwise qualify for moral rights protection.

Duration and Emerging Challenges

The duration of copyright protection also varies significantly between human-authored and computer-generated works. While human-authored works typically receive protection for the author’s life plus 50-70 years, computer-generated works in jurisdictions that recognise them receive shorter terms. This disparity affects the commercial value and long-term protection of AI-generated content.

Recent developments in deepfake technology and digital replicas have presented new challenges to copyright and personality rights. AI systems can now generate convincing replicas of real people’s voices, images, and performances, potentially infringing on both copyright and personality rights. This has prompted some jurisdictions to consider new legal frameworks specifically addressing AI-generated replicas.

The EU’s Copyright Directive attempts to address some of these challenges through specific provisions for text and data mining. These provisions allow particular uses of copyrighted material for computational analysis while preserving rights holders’ ability to opt out of such uses. Nevertheless, the practical implementation of these provisions remains complex and varies among EU member states.

For creators and businesses, these copyright challenges require careful attention to documentation and attribution. Organisations must develop clear policies for using AI tools while preserving their ability to claim copyright in the resulting works. This often involves maintaining detailed records of human input and creative decisions throughout the AI-assisted creative process.

Patent Law and AI Inventions

Patent law presents unique challenges when applied to AI inventions and AI-generated innovations. The fundamental requirement that patents name a natural person as the inventor creates immediate complications for inventions conceived primarily or entirely by artificial intelligence systems.

The DABUS Case and Global Responses

The DABUS case has become the defining example of these challenges. Dr Stephen Thaler attempted to file patent applications in multiple jurisdictions listing his artificial intelligence system, DABUS, as the inventor. The USPTO, European Patent Office, and UK courts all rejected these applications, maintaining that only natural persons can be inventors under current patent laws.

Nevertheless, South Africa’s acceptance of the DABUS patent created an international precedent that highlights the inconsistent global approach to AI inventions. This decision, while controversial and legally isolated, suggests that some jurisdictions may be willing to adapt their patent systems to accommodate AI-generated innovations.

AI-Generated vs. AI-Assisted Inventions

The distinction between AI-generated inventions and AI-assisted inventions has become critical for patent prosecution. When human inventors use AI tools to assist in research, analysis, or design processes, the resulting inventions may still qualify for patent protection if the human contribution meets the threshold for inventorship. Nevertheless, determining this threshold remains challenging and often requires case-by-case analysis.

Patentability Standards and AI Technologies

Patent applications involving AI technologies are subject to additional scrutiny regarding the standards for novelty, non-obviousness, and industrial applicability. Patent examiners must evaluate whether AI-assisted inventions meet these traditional requirements while considering the unique capabilities and limitations of AI systems.

Strategic Considerations for Businesses

For pharmaceutical and technology companies using AI for research and development, these patent law challenges create strategic considerations. Many organisations are documenting human involvement in AI-assisted research to preserve patentability while also exploring trade secret protection for innovations that may not qualify for patent protection.

Implications for Innovation and Future Legal Developments

The current patent system’s treatment of AI inventions has practical implications for innovation incentives and technology transfer. If AI-generated innovations cannot receive patent protection, inventors may rely more heavily on trade secrets, potentially reducing public disclosure and knowledge sharing that patents traditionally encourage.

Future developments in patent law may include modifications to inventorship requirements or the creation of new categories of protection for AI-generated innovations. Nevertheless, such changes would require significant legislative action and international coordination to maintain consistency in global patent systems.

Business and Contractual Considerations

Businesses implementing AI technologies must operate complicated contractual and liability considerations that existing legal frameworks don’t fully address. The allocation of responsibility between AI developers, platform providers, and end users remains one of the most pressing practical concerns for organisations adopting AI tools.

Major AI platforms have developed terms of service that attempt to address IP ownership and liability issues, though these terms vary significantly across providers. OpenAI’s terms for ChatGPT, for example, assign rights in AI-generated outputs to users while requiring compliance with applicable laws and third-party IP rights. Nevertheless, these contractual provisions don’t resolve underlying questions about the copyrightability or patentability of AI-generated content.

Analysis of major AI platform terms reveals common patterns and essential differences:

ChatGPT (OpenAI):

• Users retain rights to their inputs and receive rights to outputs

• Platform disclaims responsibility for IP infringement by outputs

• Users are responsible for compliance with applicable laws

Midjourney:

• Users receive rights to the generated images under paid plans

• Limited rights for free tier users

• Platform retains a broad license to use and display all generated content

Stable Diffusion:

• Open-source model with various licensing terms depending on implementation

• Users are responsible for ensuring compliance with training data licenses

• Commercial use restrictions may apply depending on deployment

For businesses, these contractual frameworks create several practical challenges. Organisations must assess their exposure to IP infringement claims when using AI-generated content in a commercial context. This includes evaluating whether AI outputs might inadvertently reproduce copyrighted material from training datasets.

Insurance and indemnification considerations have become increasingly important as IP litigation involving AI systems continues to grow. Traditional professional liability and intellectual property insurance policies may not adequately cover AI-related risks, prompting some organisations to seek specialised coverage or negotiate specific indemnification terms with AI providers.

Best practices for documenting human contribution in AI-assisted creative processes include:

• Maintaining detailed records of human input and creative decisions

• Documenting the selection and refinement of AI-generated outputs

• Preserving evidence of substantial human modification or enhancement

• Establishing clear policies for AI tool usage within organisations

• Training employees on IP considerations when using AI systems

Legal teams are developing new contract provisions to address AI-specific risks, including clauses that allocate liability for IP infringement, establish ownership rights in AI-assisted creations, and require disclosure of AI tool usage in specific contexts.

Regulatory Responses and Legal Developments

Governments worldwide are actively developing regulatory responses to address the intersection of AI and intellectual property. These efforts reflect both the urgency of current legal uncertainties and the recognition that existing IP laws may require significant updates to address AI technologies effectively.

The European Union has taken a comprehensive approach through its AI Act, which includes provisions affecting IP rights and transparency requirements. The Act requires specific AI systems to disclose information about their training data and contains provisions that may impact the use of copyrighted material for AI training. Implementation of these requirements began in 2024, with full compliance required by 2026.

The United Kingdom conducted extensive consultations on AI and intellectual property from 2021 to 2022, exploring potential reforms to accommodate AI-generated works. While initial proposals suggested broader recognition of computer-generated works, the government ultimately decided to maintain current requirements for human authorship while continuing to monitor developments.

The U.S. Copyright Office issued comprehensive guidance in 2023, clarifying its position on the registration of AI-generated works. The guidance reaffirmed that works produced by machines without human authorship cannot be copyrighted, while providing examples of AI-assisted works that may qualify for protection if they demonstrate sufficient human creativity and originality.

Japan has adopted a relatively flexible approach, allowing AI training on copyrighted works under certain circumstances while maintaining traditional authorship requirements for copyright protection. This approach reflects Japan’s strategy to balance innovation in AI development with the protection of creators’ rights.

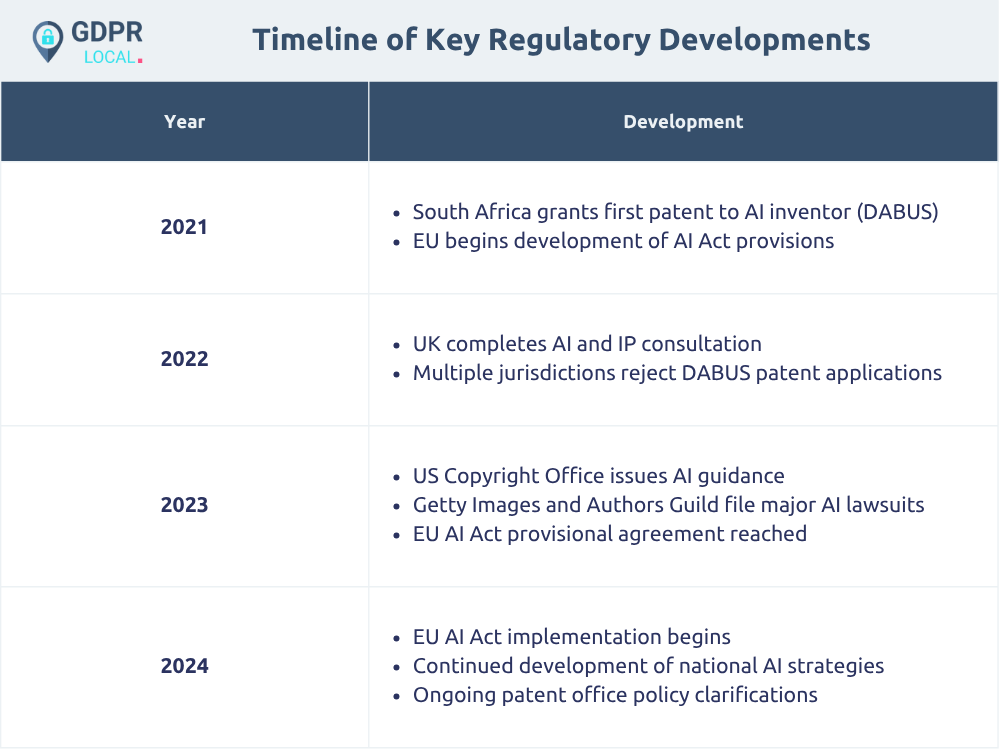

Timeline of key regulatory developments:

Emerging legislation in Australia, Canada, and other jurisdictions suggests a global trend toward maintaining human authorship requirements while developing new frameworks for regulating AI technology. These developments indicate that comprehensive reform of IP laws to accommodate AI may require several more years of policy development and international coordination.

The regulatory environment continues evolving rapidly, with new guidance and policy proposals emerging regularly. Organisations must monitor these developments closely and adapt their AI implementation strategies accordingly.

Future Outlook and Best Practices

The evolution of IP laws to address AI-specific challenges is expected to accelerate between 2025 and 2030 as the limitations of current frameworks become increasingly apparent. Legal experts predict that new categories of protection may emerge specifically for AI-generated content, potentially creating sui generis rights similar to those existing for databases or semiconductor designs.

For creators and businesses seeking to protect their works from unauthorised AI training, several practical steps are emerging:

Technical Protection Measures:

• Implementing robot.txt files and terms of service that explicitly prohibit AI training

• Using watermarking and fingerprinting technologies to track content usage

• Developing content licensing platforms that facilitate legitimate AI training

Legal Strategies:

• Registering copyrights quickly to establish ownership records

• Including AI-specific terms in licensing agreements

• Joining collective licensing initiatives for AI training data

• Conducting due diligence on AI tool training data sources

• Maintaining detailed documentation of human involvement in AI-assisted creation

• Developing internal policies for AI tool usage and IP creation

• Seeking legal review of AI-generated content before commercial use

Emerging technologies, such as blockchain, are beginning to play a role in provenance tracking and rights management for digital content. These systems may provide new mechanisms for establishing ownership and tracking usage of creative works in AI training contexts.

The development of industry standards for AI training data licensing represents another important trend. Organisations like Creative Commons and various industry groups are working to establish frameworks that balance creators’ rights with AI developers’ needs for training data.

Recommendations for staying compliant as legal frameworks evolve:

1. Establish AI governance policies that address IP considerations and require legal review of AI implementations

2. Monitor regulatory developments in relevant jurisdictions and adapt practices accordingly

3. Invest in human creativity documentation to preserve IP rights in AI-assisted works

4. Consider specialised insurance coverage for AI-related IP risks

5. Engage with industry initiatives, developing standards for responsible AI development and deployment

Conclusion

The intersection of AI and intellectual property will continue evolving as technology advances and legal frameworks adapt. Organisations that proactively address these challenges while maintaining focus on innovation and compliance will be best positioned to succeed in the emerging environment.

As artificial intelligence continues transforming how we create, innovate, and protect intellectual property, understanding the legal implications has become essential for businesses across all industries. The current legal environment requires careful navigation, but with proper planning and expert guidance, organisations can harness the power of AI while protecting their intellectual property interests.

For businesses implementing AI technologies, the key to success lies in striking a balance between innovation and legal compliance. This means staying informed about evolving regulations, documenting human creativity in AI-assisted processes, and working with IP professionals to develop comprehensive strategies that address both current requirements and anticipated future developments.

The future of AI and intellectual property will be shaped by ongoing dialogue between technologists, legal experts, policymakers, and creators. By participating in this conversation and taking proactive steps to address IP considerations, businesses can help shape a legal framework that supports both innovation and creators’ rights in the age of artificial intelligence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can AI-generated content receive intellectual property protection?

In most jurisdictions, AI-generated content cannot receive traditional intellectual property protection, such as copyright, unless it involves significant human intervention. Copyright laws generally require human authorship or creativity. However, some countries, like the United Kingdom, provide limited protection for computer-generated works where no human author can be identified, with a protection term of 50 years.

2. Who can be named as the inventor in patent applications involving AI inventions?

Patent laws worldwide typically require that the inventor be a natural person. AI systems cannot be recognised as inventors because they lack the legal personality required to hold such a status. Human inventors who utilise AI tools to assist in creating inventions may still qualify as inventors if they make sufficient contributions. The controversial DABUS case highlighted this issue, with most patent offices rejecting AI as an inventor, except for South Africa.

3. What are the risks of intellectual property infringement when using AI systems?

AI systems are often trained on vast datasets that include copyrighted and other IP-protected works, sometimes without explicit permission from rights holders. This raises significant infringement risks, particularly when AI-generated outputs closely resemble or reproduce protected content. Businesses must carefully assess the training data used and implement licensing or compliance measures to mitigate these risks.