PIPEDA’s Guidelines for Obtaining Meaningful Consent

Under PIPEDA, obtaining meaningful consent for the management of personal information is a complex yet critical requirement. Meaningful consent refers to the requirement that individuals must truly understand the nature, purpose, and consequences of the collection, use, or disclosure of their personal information before they agree to it.

This blog post delves into what makes consent meaningful, highlights key principles that support this requirement, and offers practical steps that organizations can follow to ensure they are compliant.

Principles for Establishing Meaningful Consent

These are the seven principles to guide organizations in understanding what constitutes meaningful consent. This summary aims to provide a clearer understanding of each principle.

Emphasize Key Elements

For meaningful consent, organizations must clearly and effectively emphasize key elements of their privacy practices. This includes specifying what personal information is collected, with whom it’s shared, the purposes for its use, and potential risks of harm. In detail, this means transparently disclosing:

| What’s collected | The specific types of personal data gathered, whether directly or indirectly. |

| How it’s used | The precise purposes for which the data will be used, avoiding vague or misleading language. |

| Who has access | Any third parties who may receive the data and the reasons for sharing it. |

| Potential risks | Any foreseeable risks associated with the collection, use, or disclosure of the data, so they can make informed choices. |

It’s crucial that this information is presented upfront, in a way that’s easily accessible and understandable to individuals, allowing them to make informed decisions about their data. This approach ensures that consent is not only informed but also meaningful, aligning with best practices and legal requirements.

Allow Individuals to Control the Level of Detail They Get and When

Providing information in accessible and manageable ways is crucial for meaningful consent.

Organizations should offer information in layers or other user-controlled formats, allowing individuals to decide how much detail they want and when. Layered information involves presenting privacy information in a structured way, starting with a concise summary of the key points and then providing options to access more detailed information if desired. This flexibility supports various user preferences, from those who prefer a quick summary to those who desire an in-depth understanding at different stages of their interaction with a service. It’s essential that individuals can revisit and revise their consent decisions as needed, with full information readily available.

Provide Individuals with Clear Options to Say ‘Yes’ or ‘No’

Under PIPEDA, organizations must adhere to the principle of limiting collection, meaning they should only collect personal information that is necessary for the identified purposes. This principle ties into the concept of consent by ensuring that individuals are not asked to consent to the collection of unnecessary information. This means that individuals must consent only to the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information necessary for the service provided, with a choice in all other scenarios.

This choice should be clear and accessible, designated as either ‘opt-in’ or ‘opt-out’ based on specific criteria. For any essential service requirement, organizations need to justify why certain data is a condition of service, especially if it’s not apparent.

Be Innovative and Creative

Organizations are encouraged to innovate in their consent processes, utilizing digital capabilities to provide just-in-time notices, interactive tools, and customized mobile interfaces.

– Just-in-Time Notices deliver crucial privacy information precisely when it’s most relevant, such as during data entry points.

– Interactive Tools like walkthroughs, videos, and infographics make the presentation of privacy practices more engaging.

– Customized Mobile Interfaces ensure privacy notices are optimized for small screens and brief interactions, addressing the unique challenges of mobile environments. These strategies enhance user understanding and engagement in privacy decisions.

Consider the Consumer’s Perspective

Consent processes should be designed from the consumer’s perspective to ensure they are understandable and user-friendly. This involves using clear language, considering the user experience, and making information accessible across various devices. Organizations should also engage with users and experts in the design process, utilizing methods like focus groups or UI/UX consultations to refine consent practices. This approach should be adaptable to the organization’s size and the nature of the information handled.

Make Consent a Dynamic and Ongoing Process

Informed consent is a dynamic process that must adapt as organizational practices and circumstances evolve. It involves ongoing engagement with users, including interactive tools like FAQs and chatbots, to clarify and address concerns. Organizations should notify and obtain renewed consent for significant changes in data use or when introducing new practices. Regular reminders about privacy options and periodic audits of information management practices are recommended to maintain transparency and adherence to declared privacy practices.

Be Accountable: Stand Ready to Demonstrate Compliance

Organizations must be able to demonstrate compliance with consent requirements, proving that their processes are clear and meaningful for their target audience. This includes showing regulators or in response to complaints that they have actively implemented and followed the principles outlined in the relevant privacy legislation. Accountability also involves regular checks and potentially showcasing these efforts during audits or regulatory reviews, with expectations varying based on the organization’s size and the nature of the personal data handled.

Determining the Appropriate Form of Consent

In determining the appropriate form of consent—express or implied—organizations must evaluate the sensitivity of the data, the individual’s reasonable expectations, and potential harm.

– Express consent means a clear, affirmative action by the individual, such as checking a box, signing a form, or clicking “I agree.”

– Implied consent can be inferred from the individual’s actions or inaction, but it should only be relied upon for less sensitive information and uses that are clearly in line with the individual’s reasonable expectations.

Express consent is generally required for sensitive data, unexpected uses, or activities posing a significant risk. The definition of sensitive information isn’t fixed; it varies with context. For instance, health, financial, and biometric data are typically sensitive, but even less sensitive data can become critical when linked with other information.

For example, a phone number may be considered less sensitive in general, but it could become more sensitive if it’s used to track an individual’s location or behavior. Organizations should also assess how the individual would view the data usage, considering the possibility of harm, which includes physical, reputational, or other impacts. This consideration should guide whether consent should be explicit to protect individual rights effectively.

Consent and Children

Consent for children regarding their personal information is complex due to their varying levels of cognitive and emotional development. Legislation often requires that consent come from a parent or guardian, especially for children under 13, as they may not grasp the implications of their privacy decisions. For older minors capable of providing consent, organizations must consider their maturity level and ensure their consent processes are age-appropriate and understandable. This means using clear and concise language, avoiding complex legal jargon, and providing explanations in a format that is easy for young people to comprehend. Demonstrating that these processes lead to meaningful consent is crucial, aligning with established privacy guidelines.

“No-go Guidance”

The “No-go Guidance” under PIPEDA’s Section 5(3) stipulates that personal information can only be processed if a reasonable person would consider it appropriate. The guidance emphasizes the necessity for processing to be reasonable, regardless of consent, evaluating factors such as the sensitivity of the information and the legitimacy of the business need.

Accordingly, the No-go Guidance identifies six specific areas considered non-compliant with PIPEDA, which the OPC views as boundaries that should not be crossed.

– Collection, use or disclosure that is otherwise unlawful.

– Profiling or categorization that leads to unfair, unethical or discriminatory treatment contrary to human rights law.

– Collection, use or disclosure for purposes that are known or likely to cause significant harm to the individual.

– Publishing personal information with the intended purpose of charging individuals for its removal.

– Requiring passwords to social media accounts for the purpose of employee screening.

– Surveillance by an organization through audio or video functionality of the individual’s own device.

Organizations must adhere to these guidelines to ensure their data practices respect privacy laws and maintain public trust.

What Should You Do?

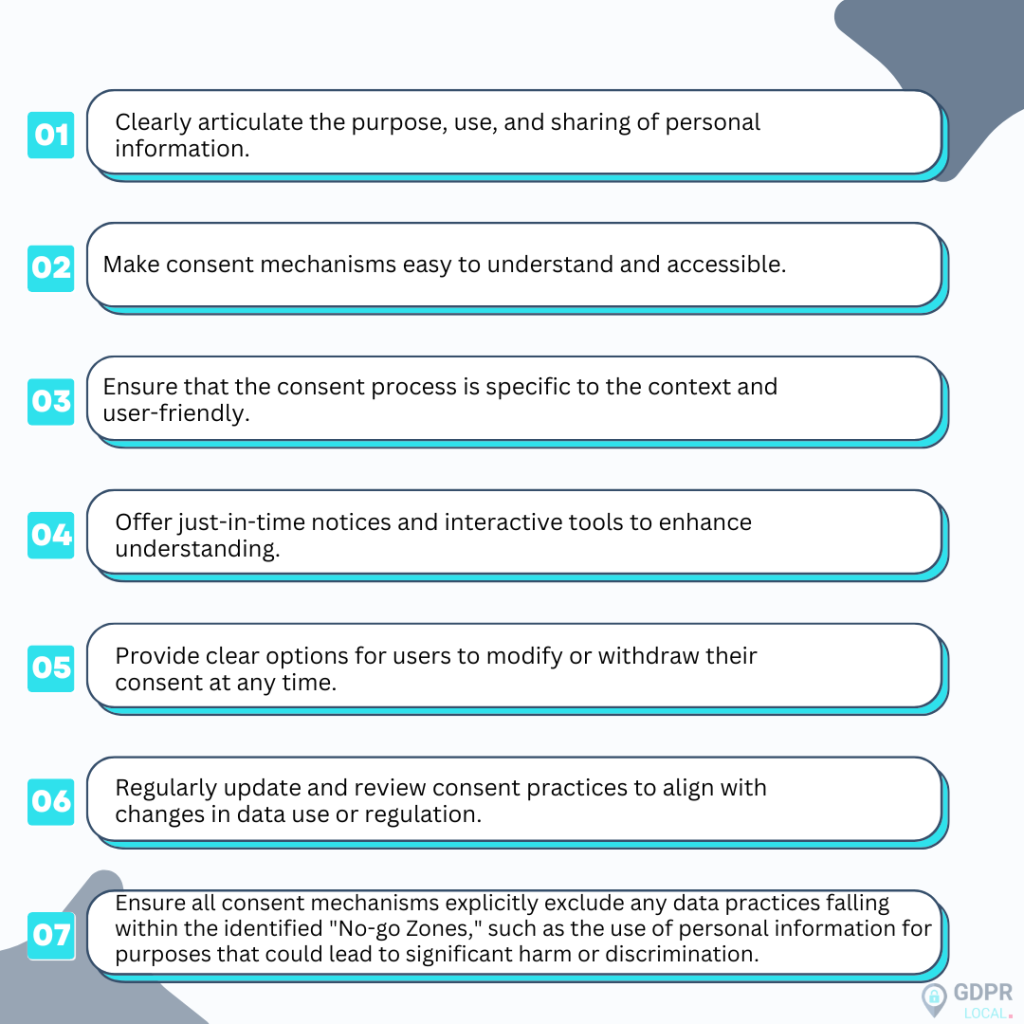

To effectively obtain meaningful consent, a company should:

How Can We Help?

Our consultants can review your consent mechanisms and forms, providing expert advice to ensure they meet legal requirements and embody best practices. With our guidance, your organization can navigate the complexities of meaningful consent, enhancing user trust and compliance. Let us help you strengthen your privacy processes for better consumer engagement and legal adherence.