Privacy Laws Around the World – Detailed Overview

“Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”, said Edward Snowden, is arguably one of the most popular privacy quotes, and rightfully so.

To thoroughly understand privacy as a concept, it’s important to know the broad definition: privacy is the right to be let alone, or freedom from interference or intrusion.

Privacy International, as a UK-based registered charity that defends and promotes the right to privacy, explains it as “having a choice” – the right to decide who we tell what, to establish boundaries, to limit who has access to our bodies, places and things, as well as our communications and our information. It allows us to negotiate who we are and how we want to interact with the world around us, and to define those relationships on our own terms.

And if we look at privacy, the definition has drastically changed in recent decades, always following the latest technological advancements and developments. Here’s a brief look at how our relationship with data has changed over the years.

2000-2004: The Early Days

In the early days of the internet, users were more concerned with connection speeds than data collection. Companies like Google processed user data collectively, not individually. Privacy concerns were minimal as the digital footprint of the average person was still relatively small.

2005-2011: The Turning Point

This era marked a huge turning point, with the rise of social media (starting with Facebook) and the launch of the first iPhone. Companies realised individual data was a goldmine for targeted advertising. Google acquired YouTube (2006) and DoubleClick (2007), creating new avenues for tracking user activity. As we started sharing more of our lives online, the first data breaches began to sound the privacy alarm.

2012-2017: The Necessity for Regulation

The alarm bells grew louder as massive data breaches became commonplace. From Yahoo’s three-billion-account breach to the theft of millions of medical records, the public’s trust was shaken. People finally understood that their online behaviour created a trail of personally identifiable information (PII) that could be stolen, misused, or unethically exploited. By 2016, 86% of internet users reported taking steps to mask their digital footprint, though many lacked the knowledge to do so effectively.

2018-Present: Regulation vs. Reality

Major events like the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the enforcement of Europe’s GDPR marked another turning point. Both people and governments began to formally acknowledge digital privacy as a fundamental right.

However, a gap between awareness and action persists. Despite stricter laws, many people feel they haven’t gained more control. High rates of identity theft continue, and users often engage in risky behaviour, such as reusing passwords or ignoring privacy policies, out of convenience or “consent fatigue.”

Privacy matters, irrespective of whether you have something to hide. It upholds personal freedoms, protects against the abuse of information, enhances security, and preserves personal dignity. Protecting it means ensuring a fair, free and respectful global society.

Rise of Global Data Protection Frameworks

The rise of global data protection frameworks marks a significant worldwide trend, with 144 countries, covering 79% of the global population, projected to have data privacy laws by early 2025.

This movement toward greater accountability is driven by increased public awareness, government initiatives to regulate data, and the widespread influence of the EU’s GDPR as a model for enhanced individual rights.

As these frameworks evolve, they now face emerging challenges, including the privacy implications of AI and the critical need for interoperable regulations that facilitate secure data transfers across international borders.

Growing Role of Technology in Privacy Enforcement

Technology now plays a foundational role in the operational enforcement of global privacy regulations. Organisations deploy data discovery and mapping tools to scan their entire digital infrastructure, from local servers to cloud environments.

This process identifies and classifies personal and sensitive information, providing a comprehensive data inventory required by many laws. Consent management platforms automate the collection and documentation of user permissions for data processing activities, creating a verifiable audit trail.

Complex procedures such as Data Subject Access Requests are managed through automated workflows that handle identity verification, data collation, and secure delivery of information to the individual. Beyond reactive compliance, advanced Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are being integrated directly into systems.

Techniques like differential privacy introduce statistical noise to datasets before analysis to protect individual identities, while homomorphic encryption allows computation on encrypted information without ever decrypting it.

This suite of technologies forms a technical framework for organisations to manage their legal obligations, conduct risk assessments, and demonstrate their data protection measures to regulatory authorities.

Understanding Data Privacy: Key Concepts under GDPR

What is Personal Data

When you hear “personal data,” you probably think of the obvious things: your name, email address, and maybe your phone number. While that’s correct, the true scope of personal data is far broader and includes many details you might not expect.

Under data protection laws like the GDPR (Article 4), personal data is any information that can be used to identify a living person, either directly on its own or by connecting it with other pieces of information.

This expands the definition to a surprising range of identifiers. Think about your device’s IP address, your work timecard records, your location history, or even opinions written about you in a performance review.

It also covers biometric data, such as your fingerprints and genetic information, as well as any content you create, including social media posts and photos.

The key is whether a piece of information, or a combination of them, can be linked back to you as a unique individual.

Personal Data Examples

Includes any information that can identify a person, directly or indirectly.

• A name, address, or telephone number.

• An email address.

• A photograph where someone is recognisable.

• An IP address from a computer or mobile device.

• Information about online purchases or browsing activity.

Not Personal Data

The GDPR’s rules for protection do not extend to the following types of information.

• Data about organisations or companies (legal entities).

• Data relating to deceased people.

Special Categories of Personal Data (Article 9 GDPR)

A specific list of data types that is given extra legal protection due to their potential for misuse.

• Race or ethnic origin.

• Political opinions.

• Religious or philosophical beliefs.

• Trade union membership.

• Genetic data.

• Biometric data is used for unique identification (like a fingerprint).

• Data concerning health.

• Information about a person’s sex life or sexual orientation.

Sensitive Personal Data

This group includes data not officially listed in Article 9 but still considered highly private and requiring careful handling.

• Financial data, such as income or payment records.

• Location data from mobile devices.

• Information about electronic communications.

• National identification numbers.

Core Principles of Data Protection

The data protection laws of the United Kingdom and the European Union, the UK GDPR and EU GDPR, are both built upon the same seven foundational principles.

For any organisation handling personal information under these regulations, these rules establish the minimum standard.

They provide the framework for responsible data management and are the measure of compliance within these specific legal systems.

• Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency: The first principle has three parts. Processing must be lawful, meaning it is based on a legitimate legal ground. It must be fair, meaning organisations handle data in ways people would reasonably expect and do not use it for purposes that could have an unjustified negative effect on them. It must be transparent, meaning individuals are given clear, open, and honest information from the start about who is processing their data and why.

• Purpose Limitation: Organisations must be specific about why they are collecting personal data and what they intend to do with it. The information collected for one stated purpose cannot be used for a new, incompatible purpose. This prevents function creep, where data is gradually used for more and more reasons beyond what the individual originally agreed to.

• Data Minimisation: An organisation must only collect and process the personal data that is adequate and

relevant for its stated purpose. It should hold the minimum amount of information necessary to achieve its goal. This means avoiding the collection of excessive or unnecessary data, as it may not be useful later.

• Accuracy: Personal data must be accurate and, where needed, kept up to date. Organisations must take every reasonable step to correct or delete information that is inaccurate or incomplete. This principle acknowledges that incorrect data can have damaging consequences for individuals.

• Storage Limitation: Organisations are not permitted to keep personal data indefinitely. Information must be deleted once the purpose for which it was collected has been fulfilled. An organisation must have policies in place to define retention periods and to justify why data is kept for a certain length of time.

• Integrity and Confidentiality (Security): This principle requires organisations to protect personal data against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction, or damage. This is the core security principle, demanding appropriate technical and organisational measures, such as encryption, access controls, and staff training, to keep data safe.

• Accountability: The accountability principle makes an organisation responsible for complying with all the other principles. It must be able to demonstrate its compliance. This involves maintaining records of processing activities, implementing data protection policies, conducting impact assessments, and having a culture of data protection throughout the organisation.

The accountability principle requires you to demonstrate compliance, not just follow the rules. See how gpdrlocal.com offers expert guidance to build and manage your GDPR compliance framework.

Data Controller vs Data Processor

The Data Controller

The data controller is the organisation or individual that determines the reasons and methods for processing personal data. They hold the primary responsibility for what happens to the information and for complying with the law.

A controller makes the key decisions, from what data to collect about a person to how long that data will be kept. They define the entire purpose of the data processing activity.

This role includes the direct duty to handle requests from individuals exercising their privacy rights, such as the right to access or delete their data. The controller is the main party accountable to regulatory authorities for any compliance failures.

The Data Processor

The data processor is a separate organisation or individual that processes personal data on behalf of the controller. They act only on the controller’s documented instructions and do not own the data.

Their activities could include storing files on a cloud server, running an email marketing campaign, or managing payroll for another company’s employees. They do not have any say in the original purpose for collecting the data.

A processor’s primary legal obligation is to implement appropriate security measures to protect the data it handles. They must also inform the controller without undue delay upon discovering a data breach.

The Controller-Processor Relationship

A legally binding contract must govern the connection between a controller and a processor. This document is often called a Data Processing Agreement (DPA).

This agreement sets out the specifics of the processing, including its subject matter, duration, and the security measures required. It confirms the processor will only act on the controller’s instructions and outlines the duties of both parties.

A Data Processing Agreement (DPA) is a must for any business that shares data. Get fully compliant DPAs with the help of gpdrlocal.com.

Cross-border Data Transfers and Adequacy

A cross-border data transfer occurs anytime personal data is sent from a country covered by the UK or EU GDPR to a country outside of that legal territory. These international transfers are strictly regulated to protect individuals’ privacy rights.

The fundamental rule is that the high level of protection afforded to data under the GDPR must travel with the data. An organisation cannot simply move information to a country with weaker laws without a proper legal safeguard in place.

Adequacy Decisions

An adequacy decision is a formal finding that a third country’s legal framework provides a comparable level of data protection to the GDPR. The European Commission makes this determination for the EU GDPR, and the UK government makes it for the UK GDPR.

When a country is deemed adequate, data can flow freely to it from the respective GDPR region. This creates a secure and straightforward data bridge, removing the need for organisations to implement additional transfer tools.

The list of adequate countries includes places like Japan, Switzerland, and Canada for certain commercial activities. The EU has also granted the UK an adequacy decision, which is vital for post-Brexit data flows and is set for review in 2025.

What Happens Without an Adequacy Decision

Most countries in the world do not have an adequacy decision. For data to be transferred to these locations, organisations must use alternative legal safeguards.

The most common alternative is the use of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). These are model data protection clauses, pre-approved by the authorities, that are inserted into the contract between the data exporter and the data importer.

For transfers within a multinational corporate group, organisations can use Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs). These are internal codes of conduct that define the group’s data protection policies and are approved by a data protection authority.

Mismanaging Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) can lead to significant fines. Get expert help with cross-border data transfer rules at gpdrlocal.com.

Regional and National Privacy Laws: A Comparative Overview

Europe and the UK: The General Data Protection Regulation

The UK GDPR and the EU GDPR share a common foundation, as the UK effectively incorporated the EU GDPR’s text into its domestic law. This happened at the end of the Brexit transition period, creating a UK version of the regulation that mirrors the original.

The core definitions for key terms like ‘personal data’, ‘data controller’, and ‘data processor’ are identical across both laws, which are the fundamental concepts that underpin the regulations and are aligned.

The rights provided to individuals, such as the right to access or correct their information, are the same under both frameworks. Organisations also have the same primary obligations, including the requirement to report data breaches and conduct impact assessments.

Both legal frameworks share the same objective. Their purpose is to provide a high level of protection for personal information and to unify data privacy rules within their respective territories.

Material Scope: What the GDPR Covers

The GDPR applies to the processing of personal data wholly or partly by automated means. It also covers non-automated processing if the data forms part of a structured filing system.

The rules apply to almost any modern handling of personal information, from a customer database to a website’s analytics. The law does not apply to processing for purely personal or household activities.

Territorial Scope: Where the GDPR Applies

The regulation has an extensive reach, applying to organisations both inside and outside the European Union. Its applicability is based on the location of the individuals whose data is being processed, not just the location of the company.

First, the GDPR applies to any organisation established in the EU that processes personal data, regardless of where the actual processing takes place.

Second, it applies to organisations outside the EU if they offer goods or services to individuals in the EU or monitor their behaviour.

Key Requirements: Consent, DPOs, and DPIAs

Beyond the core principles, the GDPR establishes specific obligations for organisations. Three of the most significant requirements involve obtaining proper consent, appointing a data protection expert, and assessing processing risks.

The Standard for Valid Consent

When an organisation relies on consent to process personal data, it must meet a high standard. Consent must be a freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the individual’s wishes, given by a clear affirmative action.

Pre-ticked boxes or inaction do not count as valid consent. The request for consent must be separate from other terms and conditions, and it must be as easy for an individual to withdraw their consent as it was to give it.

The Role of the Data Protection Officer (DPO)

A Data Protection Officer is an independent data protection expert responsible for advising an organisation on its compliance obligations. The DPO monitors internal compliance and acts as a point of contact for individuals and regulatory authorities.

An organisation must appoint a DPO if it is a public authority, or if its core activities involve large-scale, regular monitoring of individuals or large-scale processing of special categories of data. The DPO’s role is to guide and oversee the organisation’s data protection strategy.

Assessing Risk with a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

A Data Protection Impact Assessment is a process for identifying and minimising the risks of a data processing operation. It is a mandatory step before an organisation begins any new project that is likely to result in a high risk to individuals’ rights and freedoms.

A DPIA describes the planned processing and its purposes, assesses its necessity and proportionality, and helps manage the risks to the rights of individuals by identifying and implementing protective measures. This is a key part of the accountability principle, showing that an organisation has proactively considered the potential impact of its activities.

Explore flexible DPO-as-a-Service solutions from gpdrlocal.com to meet your obligations.

Enforcement and Fines

Each country covered by the GDPR has a supervisory authority responsible for enforcing the law. These authorities have significant powers to investigate organisations and to issue corrective orders.

They can conduct audits, demand access to information, and order a temporary or permanent ban on data processing. This ensures they have the tools to make organisations comply with the regulation.

A complete list of national data protection authorities for the United Kingdom and all countries within the European Economic Area (EEA), which includes all EU member states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

United Kingdom

•United Kingdom: Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) – https://ico.org.uk/

European Union (EU) Member States

• Austria: Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde

• Belgium: Data Protection Authority

• Bulgaria: Commission for Personal Data Protection – КЗЛД

• Croatia: Agencija za zaštitu osobnih podataka (AZOP) – AZOP

• Cyprus: Office of the Commissioner for Personal Data Protection – http://www.dataprotection.gov.cy/

• Czechia: Úřad pro ochranu osobních údajů (ÚOOÚ) – Úřad pro ochranu osobních údajů

• Denmark: Datatilsynet – Datatilsynet

• Estonia: Andmekaitse Inspektsioon (AKI) – Andmekaitse Inspektsioon

• Finland: Tietosuojavaltuutetun toimisto – Tietosuojavaltuutetun toimisto

• France: Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) – CNIL

• Germany: Der Bundesbeauftragte für den Datenschutz und die Informationsfreiheit (BfDI) – BfDI

• Greece: Hellenic Data Protection Authority (HDPA) – | Αρχή Προστασίας Δεδομένων Προσωπικού Χαρακτήρα

• Hungary: Nemzeti Adatvédelmi és Információszabadság Hatóság (NAIH) – https://www.naih.hu/

• Ireland: Data Protection Commission (DPC) – Data Protection Commission

• Italy: Garante per la protezione dei dati personali (GPDP) – Garante Privacy

• Latvia: Datu valsts inspekcija – Datu valsts inspekcija

• Lithuania: Valstybinė duomenų apsaugos inspekcija (VDAI) – Valstybinė duomenų apsaugos inspekcija

• Luxembourg: Commission nationale pour la protection des données (CNPD) – Commission nationale pour la protection des données

• Malta: Office of the Information and Data Protection Commissioner (IDPC)- IDPC

• Netherlands: Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens (AP) – Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens

• Poland: Urząd Ochrony Danych Osobowych (UODO) – UODO

• Portugal: Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados (CNPD) – CNPD

• Romania: Autoritatea Naţională de Supraveghere a Prelucrării Datelor cu Caracter Personal (ANSPDCP) – Dataprotection.ro

• Slovakia: Úrad na ochranu osobných údajov Slovenskej republiky – Úrad na ochranu osobných údajov

• Slovenia: Informacijski pooblaščenec – Informacijski pooblaščenec

• Spain: Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) – Agencia Española de Protección de Datos

• Sweden: Integritetsskyddsmyndigheten (IMY) – Integritetsskyddsmyndigheten

Other European Economic Area (EEA) Countries

• Iceland: Persónuvernd – Persónuvernd

• Liechtenstein: Datenschutzstelle (DSS) – Liechtensteinische Landesverwaltung

• Norway: Datatilsynet – Datatilsynet

Fines

The GDPR is known for its two tiers of administrative fines, which are designed to be effective and proportionate. The level of the fine depends on the nature and severity of the infringement.

For less severe violations, an organisation can be fined up to €10 million or 2% of its total global annual turnover, whichever is higher. For the most serious infringements, such as violating the core principles or mishandling individual rights requests, fines can be up to €20 million or 4% of total global annual turnover.

UK GDPR vs EU GDPR: Key Differences

While built on the same foundation, the UK GDPR and EU GDPR have distinct legal and operational differences.

• Territorial Scope: The UK GDPR governs the data processing of individuals within the United Kingdom. The EU GDPR regulates the data processing of individuals within the European Economic Area (EEA).

• Supervisory Authority: The sole regulator for the UK GDPR is the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The EU GDPR is enforced by independent supervisory authorities in each member state, such as France’s CNIL or Ireland’s DPC.

• International Data Transfers: The UK is now a ‘third country’ to the EU, requiring an EU adequacy decision for data to flow from the EU to the UK. The UK government makes its own independent adequacy decisions for transfers from the UK to other countries.

• Future Legislation: The UK can amend its data protection laws independently of the EU. Legislation like the UK’s Data Protection and Digital Information Act introduces changes that create growing divergence from the EU’s rules.

• National Law Exemptions: The UK Data Protection Act 2018 contains broader exemptions than many EU national laws. These are most notable in areas of national security, defence, and immigration.

• Age of Consent: The age for valid consent from a child for online services is fixed at 13 in the UK. The EU GDPR sets a baseline of 16, which member states can choose to lower to 13.

Learn about EU and UK Representation (Article 27) services at gpdrlocal.com.

United States of America

The United States does not have a single, all-around data privacy law at the federal level similar to the GDPR. Instead, it has a patchwork of laws at both the federal and state levels, creating a complex compliance environment. This state-led approach means an organisation’s obligations can change significantly depending on where its customers reside.

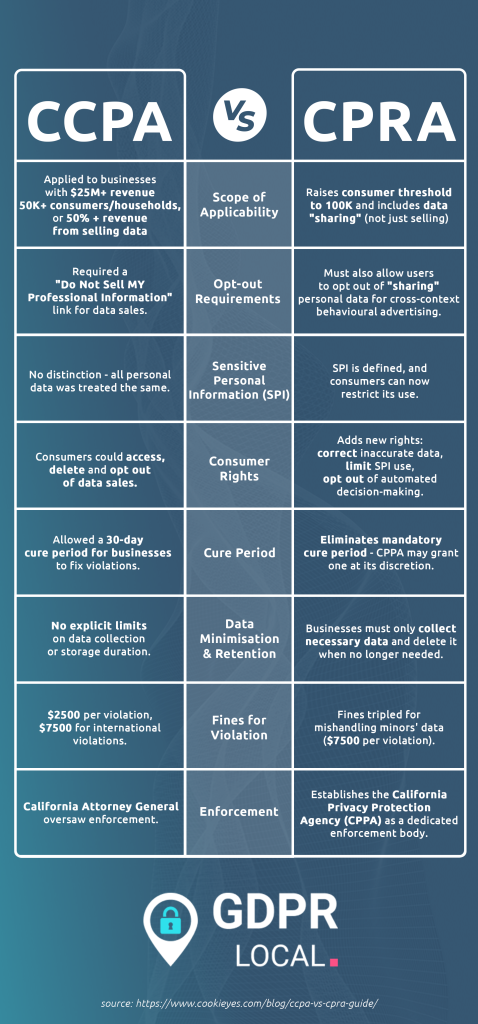

CCPA/CPRA (California)

The most influential state-level privacy law is the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which was amended and expanded by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

This law grants California consumers a set of rights over their personal information and places significant duties on businesses that collect that information.

Key provisions include the right for consumers to know what personal data is being collected about them, the right to delete that information, and the right to opt out of the sale or sharing of their personal information.

The CPRA added the right to correct inaccurate information and established the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) to enforce these rules.

• Official Agency Link: California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA)

Other Notable State Laws

Following California’s lead, several other states have enacted their own comprehensive privacy laws. Each law has its own specific thresholds, definitions, and consumer rights.

• Virginia: Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA). This law is considered more business-friendly than California’s. It grants Virginia residents rights to access, correct, delete, and opt out of the sale of their personal data and targeted advertising.

Official Law Text: https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe

• Colorado: Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) The CPA provides Colorado residents with rights similar to those in Virginia, including rights to access, correction, and deletion. It also requires businesses to conduct data protection assessments for high-risk processing activities.

Official Law Text: https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb21-190

• Utah: Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA) Utah’s law is narrower in scope and more business-friendly than the others. It gives consumers the right to access and delete their data and to opt out of the sale of their data, but does not include a right to correction.

Official Law Text: https://le.utah.gov/~2022/bills/static/SB0227.html

• Connecticut: Data Privacy Act (CTDPA) The CTDPA aligns closely with the laws in Virginia and Colorado. It provides broad rights to consumers and requires businesses to recognise user-enabled universal opt-out mechanisms for targeted advertising and data sales.

Official Law Text: https://www.cga.ct.gov/2022/act/pa/pdf/2022PA-00015-R00SB-00006-PA.pdf

Link: US State Privacy Legislation Tracker

Absence of a Federal Law

There is no single, overarching federal privacy law in the United States that governs the collection and use of all types of personal data. While sector-specific federal laws exist, such as HIPAA for healthcare information, there is no equivalent to the GDPR that applies universally.

This absence means businesses must navigate a growing number of different state laws, each with its own requirements. This fragmented legal landscape creates significant compliance challenges for organisations operating nationwide.

Canada

Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) is the country’s main federal privacy law for the private sector.

It sets the ground rules for how businesses must handle the personal information of Canadians during the course of any commercial activity.

It is important to distinguish PIPEDA from Canada’s other federal privacy law, the Privacy Act, which applies only to federal government organisations.

PIPEDA applies to all federally regulated organisations, such as banks, airlines, and telecommunications companies, across the country.

It also applies to businesses in provinces that do not have their own “substantially similar” privacy legislation.

Crucially, the law has a global reach.

PIPEDA applies to any organisation, even those outside of Canada, if it handles personal information that crosses provincial or national borders or has a “real and substantial connection to Canada“.

Overview of PIPEDA

PIPEDA’s framework is built upon ten principles that outline an organisation’s responsibilities and an individual’s rights.

1. Accountability: An organisation is responsible for the personal information it controls. It must appoint an individual who is accountable for its compliance with these principles.

2. Identifying Purposes: The reasons for collecting personal information must be determined by the organisation at or before the time of collection. These purposes should be documented and clear.

3. Consent: The knowledge and consent of an individual are required for the collection, use, or disclosure of their personal information. Consent must be meaningful for it to be valid.

4. Limiting Collection: The collection of personal information must be limited to what is necessary for the purposes identified by the organisation. The information must be collected by fair and lawful means.

5. Limiting Use, Disclosure, and Retention: Personal information can only be used or disclosed for the purposes for which it was collected, unless an individual provides new consent. It should only be kept as long as required to fulfil those purposes.

6. Accuracy Personal information must be as accurate, complete, and up-to-date as is necessary for its intended use. This helps prevent incorrect decisions being made about an individual.

7. Safeguards: Personal information must be protected by security safeguards that are appropriate for the sensitivity of the information. These measures protect data against loss, theft, or unauthorised access.

8. Openness: An organisation must make specific information about its data management policies and practices readily available. Individuals should be able to understand how their information is handled.

9. Individual Access: Upon request, an individual must be informed of the existence, use, and disclosure of their personal information. They must be given access to it and can challenge its accuracy.

10. Challenging Compliance: An individual can challenge an organisation’s compliance with the above principles. They should direct their challenge to the person accountable within the organisation.

Proposed Reforms: Bill C-27

The Canadian government is modernising its privacy framework with Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act. If passed, this bill would repeal the parts of PIPEDA that deal with personal information and replace them with three new acts:

• The Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA): This would introduce new rules for businesses, stronger enforcement powers, and higher fines for non-compliance.

• The Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act: This would create a new tribunal to review decisions made by the Privacy Commissioner and impose penalties.

• The Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA): This would be Canada’s first law to regulate the development and deployment of AI systems.

Enforcement

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) is responsible for overseeing compliance with PIPEDA. The OPC’s role is to investigate complaints, conduct audits, and promote awareness of privacy issues. Under the proposed CPPA, the Commissioner’s powers would be significantly strengthened to include the ability to issue binding orders and recommend substantial fines.

Official Agency Link: Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) – https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/

Provincial Laws (Quebec, Alberta, BC)

While PIPEDA is the federal law, some provinces have their own private-sector privacy legislation. These laws are considered “substantially similar” to PIPEDA and apply to commercial activities that take place entirely within that province’s borders. Three provinces have enacted such comprehensive laws.

Quebec: Law 25

Quebec’s privacy law has been significantly modernised by Law 25, officially An Act to modernise legislative provisions as regards the protection of personal information. This update makes Quebec’s framework one of the strictest in North America, drawing many comparisons to the GDPR.

It introduces enhanced consent requirements, new individual rights like data portability, and mandates for privacy impact assessments. The law also establishes substantial monetary penalties for non-compliance, making it a major development in Canadian privacy.

Official Law Text: Loi sur la protection des renseignements personnels dans le secteur privé

Alberta: PIPA

Alberta’s Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) governs how provincially regulated private sector organisations handle the personal information of Albertans. The law balances an individual’s right to privacy with the reasonable need of organisations to collect and use personal data for business purposes.

Official Law Text: Personal Information Protection Act (Alberta)

British Columbia: PIPA

British Columbia also has its own Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA). This law sets out the rules for how private organisations in the province collect, use, and disclose personal information, operating on principles similar to the federal PIPEDA.

Official Law Text: Personal Information Protection Act (British Columbia)

Latin America

Brasil: Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD)

Brazil established a comprehensive data protection framework with its Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD), which came into full effect in 2021. The law created a unified set of rules for how personal data is collected, used, processed, and stored in the country, applying to both private and public sector organisations.

Inspiration from GDPR

Europe’s GDPR heavily inspired the LGPD, and the two regulations share many structural similarities. This connection means organisations familiar with GDPR principles will recognise the core concepts within the LGPD. The laws are aligned on key definitions for terms like personal data, controller, and processor.

Both frameworks are also built upon a set of data processing principles, such as purpose limitation and data minimisation. This shared foundation can simplify compliance for global organisations by allowing them to adapt existing GDPR-based programs to meet the LGPD’s requirements.

Key Rights and Requirements

The LGPD grants individuals, known as data subjects, a robust set of rights to control their personal information. Key rights include the right to confirm the existence of processing, access their data, correct incomplete or outdated information, and request the anonymisation or deletion of unnecessary data.

For organisations, the law establishes several key obligations. A central requirement is the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO) to oversee data protection strategy and act as a liaison with authorities. Organisations must also maintain records of their data processing activities and report data security incidents that may create risk for individuals.

Enforcement Mechanisms

The body responsible for interpreting and enforcing the law is the Autoridade Nacional de Proteção de Dados (ANPD). The ANPD’s role is to provide guidance, conduct audits, and ensure organisations comply with the LGPD’s mandates.

The ANPD has the authority to impose a range of administrative sanctions for violations. These penalties can include warnings and, for more serious infractions, fines of up to 2% of an organisation’s revenue in Brazil for the prior fiscal year. The fines are capped at a total of R$50 million per violation.

Official Agency Link: Autoridade Nacional de Proteção de Dados (ANPD)

Other Key Latin American Jurisdictions

Beyond Brazil, several other Latin American countries have established long-standing and robust data protection frameworks. The laws in Mexico, Argentina, and Colombia are prominent examples, each with its own specific requirements for handling personal information and international data flows.

Overview of Local Laws

Mexico’s primary data protection law is the Federal Law on the Protection of Personal Data Held by Private Parties. It establishes a set of principles for data processing, including consent, data quality, and purpose limitation. The National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information and Personal Data Protection (INAI) is the authority responsible for enforcement.

Official Agency: Instituto Nacional de Transparencia, Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos Personales (INAI)

Argentina’s Personal Data Protection Act No. 25,326 is one of the oldest frameworks in the region. The European Commission has formally recognised it as providing an adequate level of protection, which simplifies data flows with the EU. The country is currently working on modernising this law to align it more closely with global standards like the GDPR. The enforcement body is the Agency for Access to Public Information (AAIP).

Official Agency: Agencia de Acceso a la Información Pública (AAIP)

Colombia’s framework is governed by Statutory Law 1581 of 2012. This law regulates the processing of personal data and places a strong emphasis on obtaining prior, express, and informed consent from individuals. The Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (SIC) is the entity that oversees and enforces these data protection rules.

Official Agency: Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio (SIC)

All three countries regulate the international transfer of personal data. The general rule is that data can only be sent to countries that provide a level of protection comparable to their own domestic standards.

For transfers to nations without an adequate protection level, these laws require other legal mechanisms to be in place. Common mechanisms include obtaining the data subject’s explicit consent for the transfer or using contractual clauses that hold the data importer to the same data protection standards. Argentina’s adequacy status with the EU is a notable facilitator for transfers to and from that region.

Asia-Pacific

The Asia-Pacific (APAC) region presents a complex and developing data privacy landscape. Unlike Europe’s unified approach, the APAC area is a mosaic of national laws, each reflecting different legal traditions and policy priorities.

This section provides an overview of the key frameworks in several of the region’s major digital economies.

We will examine the distinct approaches taken by China, Japan, India, Australia, and South Korea. Each country has developed a unique response to the challenges of data protection.

A common theme across the region is rapid modernisation, which includes landmark new legislation in China and India, as well as significant reforms of established acts in Japan and Australia.

These developments highlight the region’s growing focus on data protection in response to the expanding digital economy.

China: Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL)

China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), effective since late 2021, is the country’s first comprehensive law dedicated to this subject. It works alongside the Cybersecurity Law (CSL) and the Data Security Law (DSL) to form the foundation of China’s data governance framework.

Core Principles

The PIPL is built on a set of core principles that govern all data processing activities. Organisations must adhere to the principles of lawfulness, legitimacy, and necessity, meaning processing must have a clear purpose and be limited to the minimum scope required.

A central principle is the need for informed and separate consent, which serves as the primary legal basis for most data processing. The law also mandates transparency through clear notifications to individuals, as well as data minimisation and storage limitation to prevent excessive collection and retention.

Key Provisions and Comparisons to GDPR

The PIPL shares several key features with the GDPR, but also has distinct requirements. Like the GDPR, it has a broad extraterritorial scope, applying to organisations outside China that process the data of individuals within China to offer products or analyse their behaviour.

A major difference lies in the legal basis for processing. While the GDPR provides several equivalent legal bases, the PIPL places a much stronger emphasis on consent. For many activities, obtaining separate consent from an individual is the only valid path.

The PIPL imposes strict rules on cross-border data transfers, which is a key compliance challenge. To transfer data outside of China, an organisation must use one of three primary mechanisms: pass a government-led security assessment, obtain a certification, or sign a standard contract issued by the regulator. A separate consent for the transfer is also required.

Role of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) is the country’s primary regulator for data protection. It is responsible for the overall coordination of personal information protection efforts and for formulating specific rules and standards under the PIPL.

The CAC’s duties include conducting security assessments for cross-border data transfers and investigating major PIPL violations. The agency has the power to impose significant fines for non-compliance, which can reach up to 5% of an organisation’s annual turnover or RMB 50 million.

Official Agency Link: Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)

Japan: Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI)

Japan’s primary data protection law is the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI). This law has undergone several significant amendments in recent years to modernise its rules, strengthen protections for individuals, and align it more closely with global standards like the GDPR.

Consent and Data Sharing Rules

Under the APPI, an organisation must specify the purpose of use when collecting personal information and generally must not use it beyond that scope without the individual’s prior consent. The law sets specific rules for providing personal data to third parties.

The primary method for sharing data is to obtain the individual’s consent beforehand. Japan’s law also includes a specific opt-out mechanism. This allows businesses to provide certain personal data to third parties without prior consent, provided they have notified the individual and given them an easy way to stop the sharing. This opt-out option does not apply to sensitive personal information.

International Data Transfers

The APPI restricts the transfer of personal data to parties located outside of Japan. To conduct such a transfer, an organisation must use a valid legal mechanism. One method is to transfer data to a country that Japan’s data protection authority has recognised as having an equivalent level of protection, which includes the EU.

Alternatively, a transfer is permitted if the foreign recipient has a system in place to meet APPI standards, often established through contractual agreements. A transfer can also proceed with the individual’s informed consent, given after they have been notified about the data protection environment of the destination.

The Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) is the independent agency responsible for interpreting and enforcing the APPI.

Official Agency Link: Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC)

India: Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA)

India transformed its privacy approach with the passage of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) in August 2023. This legislation is the country’s first comprehensive data protection law, creating a unified set of rules that replaced a patchwork of older, sector-specific regulations.

Recent Developments

Since the DPDPA was enacted, the Indian government has been focused on its phased implementation across different sectors. A primary development has been the establishment of the Data Protection Board of India (DPBI). This body serves as the primary authority for adjudicating non-compliance and imposing penalties.

Organisations have been actively updating their data handling practices to align with the Act’s provisions. The government continues to release specific rules and guidance to support the law’s rollout, with enforcement timelines being closely monitored by businesses operating in India.

Consent Framework and Cross-border Transfers

The DPDPA is built around a strong consent framework. Consent must be free, specific, informed, and unambiguous, given through an explicit affirmative action. Before requesting consent, an organisation must provide the individual with a clear notice detailing the personal data to be collected and the specific purpose of the processing.

For international data transfers, the DPDPA uses a more flexible “blacklist” approach. The law permits the transfer of personal data to all countries and territories by default. The central government retains the power to restrict transfers to specific countries through official notification.

Official Law Text: Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

Australia & South Korea

Australia and South Korea both have mature data protection frameworks that have been in place for years. While South Korea is known for its detailed and strict existing rules, Australia is in the process of implementing major reforms to modernise its long-standing Privacy Act.

Australia’s Privacy Act Reforms

Australia’s data privacy framework is built on the Privacy Act 1988 and the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). In response to the digital economy, the Australian government has been advancing the most significant reforms to this Act in decades. This process aims to strengthen protections and align the law with global standards.

The proposed reforms are extensive and are expected to broaden the definition of personal information and remove the current exemption for many small businesses. Key changes also include introducing a “fair and reasonable” standard for data handling and granting individuals new rights, such as a right to erasure. The reforms are set to increase the penalty regime for serious data breaches significantly.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is the independent regulator responsible for enforcing the Privacy Act.

Official Agency Link: Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC)

South Korea’s Strict Regulatory Regime

South Korea is recognised for having one of the world’s most comprehensive and strict data privacy laws, the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA). The law is highly detailed and governs the data handling practices of both public and private sector organisations with a strong emphasis on consent.

The strictness of the regime is evident in its highly specific requirements. Organisations often must obtain separate, granular consent for the collection, use, and provision of data to third parties. PIPA is also very prescriptive about the technical and administrative security measures that must be implemented, including specific rules on encryption and access control.

The Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) acts as the central data protection authority, with strong powers to investigate violations and impose substantial fines.

Official Agency Link: Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC)

Africa and the Middle East

Data privacy in Africa and the Middle East is undergoing a period of accelerated development. Many nations across these regions are now establishing modern data protection laws. This legislative trend is driven by rapid digitalisation and the growing need to align with global data governance standards.

This section will explore key legislative frameworks that are shaping this new frontier. We will start with South Africa’s comprehensive Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA). We will then examine the latest generation of laws in the Middle East, focusing on the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia.

These laws often draw inspiration from frameworks like the GDPR, yet they include unique provisions that reflect local legal contexts and policy goals. Understanding these regional leaders is key to compliance in these dynamic markets.

South Africa: Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA)

South Africa’s primary data protection law is the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA). The act came into full effect on July 1, 2021, and it governs the processing of personal information by public and private bodies. It establishes a set of conditions for lawful processing that shares many concepts with international frameworks like the GDPR.

Core Principles

POPIA is based on eight conditions for the lawful processing of personal information. These conditions form the core of the act and set the requirements for responsible data handling. Key principles include:

• Processing Limitation: Personal information must be collected for a specific purpose, directly from the data subject, and fairly and lawfully.

• Purpose Specification: Data must be collected for a specific, explicitly defined, and lawful purpose related to the function of the organisation.

• Security Safeguards: The party processing the information must secure its integrity and confidentiality with appropriate technical and organisational measures.

• Accountability: The organisation, referred to as the “responsible party,” must ensure that all eight conditions are met for any processing it undertakes.

Enforcement and Compliance

The Information Regulator of South Africa is the independent body responsible for monitoring and enforcing compliance with POPIA. The Regulator handles complaints, conducts investigations, and has the power to issue enforcement notices to organisations that breach the Act.

Non-compliance with POPIA can lead to significant consequences. The Information Regulator can impose administrative fines of up to R10 million (approximately €500,000 or USD $540,000). Certain offences under the act can also lead to imprisonment.

Official Agency Link: Information Regulator of South Africa

UAE & GCC Countries

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have rapidly introduced modern data protection laws, with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia leading this legislative push. This trend is part of the region’s broader strategy for economic diversification and digital transformation.

UAE Federal Law No. 45

The UAE’s first comprehensive federal data protection law is the Federal Decree Law No. 45 of 2021 on the Protection of Personal Data. The law has a broad reach, applying to any organisation processing the personal data of UAE residents, even if the organisation is located outside the country. Its principles, such as purpose limitation and data minimisation, align with global standards.

The UAE Data Office was established as the federal regulator to oversee the law’s implementation. A unique aspect of the UAE’s legal landscape is that some financial free zones, like the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM), maintain their own separate data protection regimes.

Saudi Arabia’s Data Protection Law

Saudi Arabia’s Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) provides a comprehensive framework for data privacy within the Kingdom. The law places a strong focus on consent as the primary legal basis for collecting and processing personal information. The Saudi Data & AI Authority (SDAIA) is the main regulator responsible for enforcing the PDPL.

A notable feature of the PDPL is its rules on data residency. The law contains specific requirements that can restrict the transfer of certain types of data outside the Kingdom, making local data processing a key consideration for businesses operating in Saudi Arabia.

Differences Across the Region

The new data protection laws in the GCC share the common goal of protecting personal information, but their specific requirements can differ. Rules for cross-border data transfers are a key example, with each country defining its own procedures and lists of adequate jurisdictions.

These national variations reflect local legal traditions and strategic priorities. Organisations operating across the GCC cannot use a single compliance approach. They must address the specific legal requirements of each country to maintain compliance.

Challenges for Global Businesses

Operating across international borders presents unique data protection challenges. Businesses must manage the requirements of numerous laws simultaneously, creating significant operational and strategic hurdles.

Fragmented Legal Landscape

There is no single global standard for data privacy. A company may be subject to the GDPR in Europe, PIPL in China, various state laws in the U.S., and dozens of other national laws at the same time.

This legal patchwork requires organisations to develop region-specific compliance programs, which affects everything from website cookie banners to international data transfer strategies.

The cost and effort required to track and adhere to these varied regulations are substantial.

Balancing Innovation with Compliance

Modern business innovation, particularly in fields like artificial intelligence and big data analytics, often relies on access to large and diverse datasets. Data protection laws, with their principles of data minimisation and purpose limitation, create necessary boundaries around how this information can be used.

The central challenge for businesses is to develop new technologies and services while respecting these privacy rules. This requires embedding “privacy by design” into the product development lifecycle, which can add time and cost but is a critical part of building trust and meeting legal obligations.

Trends Shaping the Future of Privacy Laws

The field of data privacy is not static. Technological change, new economic models, and evolving political ideas continuously shape it. Four key trends are defining the next phase of data protection regulation around the world.

AI and Privacy Regulation

The rapid development of Artificial Intelligence is presenting new challenges to established privacy principles. AI models are often trained on vast public datasets, which can conflict with rules on purpose limitation and consent.

In response, governments are beginning to introduce AI-specific laws that require transparency in training data and fairness assessments to prevent discriminatory outcomes.

Rise of Sector-specific Privacy Rules (Finance, Health)

Beyond broad data protection laws, there is a growing movement toward more detailed rules for specific industries. Sectors that handle highly sensitive information, such as finance and healthcare, are now subject to specialised regulations.

These laws impose stricter security, data handling, and reporting requirements tailored to the unique risks of those fields.

The Push for Global Harmonisation

Organisations and governments recognise the inefficiency of the current patchwork of national privacy laws. This has led to a greater focus on creating interoperability between different legal systems. Efforts include the expansion of adequacy decisions, the use of standardised contractual clauses, and the development of global frameworks like the Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) to make international data transfers more predictable.

Digital Sovereignty and Data Localisation

A competing trend is the rise of digital sovereignty, the idea that nations should control the data generated within their borders. This principle is often driven by national security and economic interests.

It frequently leads to data localisation laws, which require companies to store or process specific data on servers physically located within the country, creating significant challenges for global data flows.

Conclusion

The world of data privacy never stands still. For any organisation operating on a global scale, understanding the legal environment is not just a compliance task; it is a core part of modern business.

The Evolving Nature of Privacy Compliance

What is compliant today might not be tomorrow. The introduction of major laws like India’s DPDPA, significant reforms in Australia, and constant updates to existing frameworks show that the rules are constantly in motion. Businesses cannot view privacy as a static checklist. Instead, they must build adaptable programs that can respond to new legal requirements as they emerge.

Importance of Staying Informed

Given this constant change, staying informed is non-negotiable. Tracking new legislation, official guidance, and enforcement actions is the only way to manage risk effectively. Resources from national data protection authorities and industry groups are indispensable tools for any compliance professional looking to keep up with their obligations.

Looking Ahead: Global Privacy in 2030

By 2030, the trends we see today will be even more defined. AI regulation will be a mature field, the tension between global data flows and data sovereignty will sharpen, and even more nations will have their own comprehensive privacy laws. The central question for the coming years is whether these different laws will converge toward a common standard or create an even more fragmented global map.

The next five years will be just as transformative as the last, making proactive privacy management a core business function for the decade to come.